- Home

- Shannon Gibney

See No Color

See No Color Read online

Text copyright © 2015 by Shannon Gibney

Carolrhoda Lab™ is a trademark of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc.

All rights reserved. International copyright secured. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the prior written permission of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc., except for the inclusion of brief quotations in an acknowledged review.

Carolrhoda Lab™

An imprint of Carolrhoda Books

A division of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc.

241 First Avenue North

Minneapolis, MN 55401 USA

For reading levels and more information, look up this title at www.lernerbooks.com.

The images in this book are used with the permission of: © Image Source/SuperStock (woman); © iStockphoto.com/DS011 (baseball); © Photoroller/Dreamstime.com (line in dirt).

Main body text set in Janson Text LT Std 10/14.

Typeface provided by Linotype AG.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gibney, Shannon.

See no color / by Shannon Gibney.

pages cm

Summary: Alex has always identified herself as a baseball player, the daughter of a winning coach, but when she realizes that is not enough she begins to come to terms with her adoption and her race.

ISBN 978-1-4677-7682-0 (lb : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-4677-8814-4 (eb pdf )

[1. Identity—Fiction. 2. Baseball—Fiction. 3. Adoption—Fiction. 4. African Americans—Fiction. 5. Self-acceptance—Fiction. 6. Family life—Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.1.G5See 2015

[Fic]—dc23

2015001619

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 – BP – 7/15/15

eISBN: 978-1-46778-814-4 (pdf)

eISBN: 978-1-46778-980-6 (ePub)

eISBN: 978-1-46778-979-0 (mobi)

FOR

THE

OTHERS

“That was the miscast summer of my barren youth which (for that short time, that short brief unreturning springtime of the female heart) I lived out not as a woman, a girl, but rather as the man which I perhaps should have been.”

—William Faulkner, Absalom, Absalom!

PROLOGUE

I am six, safe on his lap. A scorecard on the table, pencil falling out of my hand. Write the names of your teammates here, he says, moving my hand slowly left to right, As and Ns and Es smushed together slowly into words. Like magic. One page for your team, one page for the other. I nod, because I know what he wants. Not because I am listening right. You record what happens at each at bat on your scorecard. He scratches my head, how I like it. Little Kirtridge. I laugh. He makes a line from the circle past the square and asks me why he did that. I don’t know. I don’t know. But he needs some words from me. Now. That’s what happens, I say. That’s what you put down. He laughs, even though that is not all the way it works. I want to color in the circle and square, but more I want words from him. So, I put my head on his shoulder, while more words come, and he moves my pencil all around the paper. You have to keep score in order to win, he says. That is what all this adds up to, see? I close my eyes, and the dreams are almost coming now, with the words. His arms, all blankets, warm me.

CHAPTER ONE

“Go tell Dad we got to get going,” Jason commanded. He might have been only a year younger, but these days, he wasn’t trying to act like it. I didn’t like taking orders from my little brother but decided to leave it alone. I figured he had his hands full trying to negotiate Dad’s disappointment, and avoidance was his newest strategy.

Like me, Jason would do anything to avoid the look—the stern and disapproving glance Dad gave us whenever we had done wrong in the game. When you don’t play your best, you don’t just hurt yourself. You hurt me. His eyebrows would knit together, his lips even tighter than usual and he would emit this kind of energy from his eyes that could scald. I knew that Jason didn’t want to see last week’s game and his lackluster performance reflected in Dad’s eyes.

I shrugged and stared into my copy of The Scarlet Letter. “We’ve still got two hours before first pitch.” West High, which Dad had been coaching for seven years, was hoping to make it to the state tournament.

Jason glared at me, pressing his right arm into the wall. “Alex, you know how he gets when he doesn’t have enough time to do the whole warm-up.”

I remembered the game last year when I couldn’t find a tampon or pad in the entire house and we had to stop at Walgreen’s. We still got to the game very early, but Dad’s face was pinched for the next day and half. He was so irritated with me. And plus, my game was just off for seven long innings. No, Jason was right—I definitely didn’t want to go through that again, especially before such an important game. If I had to do my homework reading later tonight and postpone The Walking Dead graphic novels I’d set aside as a reward, then so be it. I stood up, reluctantly, and then pushed in my chair. “Where is he?”

Jason turned around and began stretching his other arm. “He’s down in the den, messing around with some of his files or something.”

I rolled my eyes and started walking down the long, French-tiled hallway. Dad spent hours in that den, doing God knows what. Pouring over various files, reading all his special baseball analytics newsletters, watching, cutting, and reordering video clips of our games, and most of all, checking and adding to his ever-growing battery of stats and metrics. Walking in there was like walking inside his brain; it was too intense and almost creepy.

I rounded the corner and started down the steps to the den. The cool stone against my bare feet sent shivers up my spine, and my hands grabbed my elbows. A full color print-out of last season’s metrics for both Jason and me was plastered across the right-side wall, lest either of us—or worse, Dad—committed the deadly sin of forgetting. I read the slash lines again, involuntarily:

ALEX: .311/.403/.561

JASON: .287/.377/.539

Batting average/on-base percentage/slugging percentage—three numbers that managed to be us. When I looked up, I spotted Dad, leaning over his big, gray filing cabinet, rifling through its folders. His brow was furrowed in concentration as he lifted one of them up and paged through its contents slowly and methodically. I leaned against the wall, still not in plain sight, but not really hidden either. I was relieved for some reason that he hadn’t noticed me, even though I had come here to get his attention, to tell him that we needed to go.

He pulled out an envelope that looked very worn and tattered and quite old. He ran his fingers over it gently, like he was reading braille. I don’t think I had ever seen my father handle something so carefully, and I wondered what it was. He bit his lip and then sighed. After a moment, he pulled out a letter and opened it slowly, smoothing out the folds. He was holding it at such an angle that I could not read it, but I could have made out the handwriting if I recognized it. I craned my neck out, curiosity trumping fear.

“Time to go?” His head had snapped around so quickly that I was hearing the words before seeing his eyes.

I jumped. “Yes!” I said, too brightly. “It’s twelve thirty.” I shoved my hands into my pockets.

He smiled, crammed the letter and envelope back into the folder, and slammed the cabinet closed. I jumped again at the sound.

“Sorry, honey,” Dad said, walking briskly to his chair to get his coat. “Just got caught up.” His shoulders looked a little tight, but the rest of his body looked loose, so I hoped I was off the hook. He didn’t seem angry.

He strode over to me and put his arm around my shoulder. “Shall we?”

I nodded, willing myself to lean into h

im, to make his embrace comfortable. Then we began to walk back toward the kitchen, in a kind of awkward silence. I wanted to ask him so many things. But before I could even fathom opening my mouth, we were in the kitchen, facing Jason, who was sprawled out on the floor in the runner’s stretch. “Time to go out and get a win,” Dad said, clapping his hands. Jason’s shoulders hunched, and he kind of shivered in surprise at the sharpness of the sound, almost like Dad was waking him up or something. He looked up at him and nodded grimly.

CHAPTER TWO

It was a cool late March day, with just a little bit of dew on the ground, and green just beginning to push through the hard soil. A few family and friends dotted the bleachers surrounding the field, arranging their coolers and jackets and seat-rests. I closed my eyes and inhaled deeply, trying to take it all in, and prepare myself for the first step toward winning the state tournament and, at the same time, a place on the elite club team this summer and fall. When I opened my eyes, I saw Dad walking out to meet the other coach on the pitcher’s mound. The game was against East, our crosstown rivals. The rest of us gathered as close as we dared, throwing and catching and warming up, but really just trying to listen. Dad was famous for trying to get in the heads of his rival managers.

“John,” Dad said, thrusting his hand toward the wide, lumbering man who approached him wearing a cockeyed East High cap and sweatpants that were a little too big. “So good to see you,” said Dad. “How are Katie and the kids?” He and Dad had gone to Clemson together. Dad had broken every record while he was there, while this other guy had been more of a fixture on the bench.

The man smiled warmly, and grasped Dad’s hand. “They’re great, Terry. Great. And Rachel and the kids?”

“Good, good. Everyone’s good.” Dad paused, looking down into the other team’s dugout. Lots of pale, skinny Wisconsin kids. Not much power. “Looks like you got a promising bunch this year. We’re ready for a first-rate outing today,” said Dad.

The man beamed, then slapped Dad on the back. Both of them laughed and then stared up at the sky. I got the feeling that they really didn’t have that much more to say to each other, but they had to wait for the umpire to meet them up there to begin.

“Been hearing about this center fielder you got. A girl, I hear—a black girl. Heard she’s got some legs on her, that she can hit, too.”

“That’s Alex,” Dad said, crossing his arms over his chest. “My daughter.”

The man had tiny, beady eyes, but they fluttered open. He brought his left hand to his neck and began to rub it. You could almost hear the thoughts running through his head: black daughter, white father, white mother, white brother …

“You adopted,” the man said, finally getting it. “You and Rachel.” He squinted into the sunlight. “I’m sure you told me before, and I just forgot.” The umpire was finally making his way toward them. I thanked God because all the warm-up chatter had died and no one was even throwing anymore. I could feel the tension collecting under my shoulder blades, the hiccups forming in my windpipe.

“She is a great player,” Dad said. “Phenomenal for a girl, really.”

“That so?” asked the man.

Dad shifted his weight and nodded. “She’s mixed, not black. She’s half white.”

The man nodded, and the umpire approached them about beginning the game. I exhaled as the subject changed to defining the exact location of the strike zone, how many umpires were on the field for the day, and where they would be standing.

• • •

I led off the bottom of the fifth. Since I had an on-base percentage of .403 so far this season, any inning where I was up first had possibilities. I never had power, but I could always get on base since I could hit into the holes and had speed.

We were up, three to two. They had this black pitcher who was supposed to really be something. Apparently, he had just moved to Madison a few months before. He had perfect location in the strike zone and could throw a changeup that would leave you cross-eyed as the ump called you out.

“Look for the fastball and try to adjust to anything off-speed,” Dad told me before the game. “And try to pull it to left.”

The light spring breeze felt a little too cold on my cheeks, and the sun was already too bright for my sunglasses. I lifted my bat up over my shoulder and planted my feet solidly into the ground. I knew that the pitcher had looked at the scouting report on me, too: .311/.403/.561. You didn’t get good without knowing exactly what you were up against. He brought his left hand out of the glove and went into the windup. I knew it would be a high fastball—the pitch that always looks good to hitters but rarely is. He was counting on me to swing, to give into temptation, like Jason had at the end of the last inning when he had struck out. It was coming at me, fast and hard, but I knew it was too high, so I took it. The umpire called a ball.

Out of the corner of my eye, I saw the pitcher flinch. I could hear Dad’s voice in my ear: There’s no preparation like over-preparation. Remember, every second, how lucky you are to be playing the game. Appreciate it—really feel it. Because you never know when it could all be taken away from you. I stepped back into the box. The pitcher was shaking his head at the catcher. Shaking again; they must not be on the same page. I had seen his team.

Finally, they agreed on something. He stretched and delivered. Right up the middle. He wanted that strike, no matter what. I brought the bat around fast and connected. There was a whack, and it flew over the pitcher’s head. I pumped my arms, dragged my legs toward first. Come on, Kirtridge, come on. Why was first always so incredibly far away? It blurred ahead of me while dust flew up and curled under my cleats. Come on, come on. I knew the ball had dropped in the infield, near the shortstop. I brought my foot down on the bag and ran through. My lungs tightened, constricted even though they wanted more air. The umpire stretched his arms out to either side. I exhaled. It was then that I saw the shortstop still holding the ball. I laughed. He hadn’t even tried to make the play. The pitcher lifted up his glove, motioning for the shortstop to throw him the ball. You could see he was angry from the way he moved: exaggerated and agitated. I had done my job.

I touched the base and then took a reasonable lead as my teammate stepped up to the plate. The black kid on the mound looked back at me once, over his glove, but I was confident that he wouldn’t try to pick me off. He knew exactly how fast I was now. Today, anyway, I was stronger than he was.

CHAPTER THREE

After we beat East, we went out to dinner with them. This was a league tradition, and when we won, it was a tradition my father loved. In his postgame glee, Dad insisted on paying for everyone. “To my old friend, John,” he said, raising a mug of Heineken. “A great coach and a great friend.”

You could see that John really didn’t want to raise his mug to meet Dad’s, that what he really wanted to do was get out of that pizzeria. However, he managed to stick a fake smile on his face and clink his glass with Dad’s.

Dad put his arm around John’s shoulders and squeezed hard. “This team of yours is really something, John. Really something.” Dad rarely, if ever, got drunk in public, but he often got happy. He raised his glass again. “A toast. To the team.”

John’s face became clouded, but he made the toast. The rest of his team followed with their Cokes and Sprites.

Jason and I exchanged glances across the table; I covered my mouth with my hand and hoped no one could hear me laugh. “He’s so crazy,” I said in a low voice. You couldn’t blame him for being excited, though—we were one step closer to the state tournament.

Jason shook his head. “Man,” he said, stirring the ice in his glass with his straw. “I played so bad today.”

In truth he had. 1 for 5, 2 SOs, 0 BoBs, 1 E, 0 R. I leaned toward him. “Look, all you have to do is adjust your stance a bit. Keep your shoulder in longer. You’re bailing out.” Dad would have this all on film and would no doubt make Jason watch all his at bats in slow motion high def tomorrow in the den.

J

ason drummed his fingers on the table, eyes drooping. His closely-cropped blond hair barely covered up a welt on his head that he had gotten from a badly played grounder a few games ago. “Don’t you ever wonder if this is what you’re supposed to be doing?”

I stared at him: his perfectly ironed jersey, his big ears. “What do you mean?”

“I mean the game. At this level, all the time.” He threw up his hands. “Alex, you’re sixteen, I’m fifteen, and we practice three or four hours a day. Crazy.”

I couldn’t believe what he was saying. “That’s what it takes to be the best, Jason.” I put my hand over his, stopping his drumming. I leaned toward him and whispered, “And we are the best. Maybe not right now. Everyone has slumps. You’ll pull out of it. The numbers will turn around.”

He drew his hand away and shook his head. “I’m sick of being a slash line. I don’t love it like you do,” he said. His gray eyes looked away from me.

We ran four miles a day at five thirty every morning and lifted weights in the basement when we got home from school. Since I was a girl, Dad said I had to work twice as hard to develop strength, so I lifted ten pounds more than Jason and at more reps. Practice was an hour and a half after weight lifting and usually lasted for two hours, four days a week. I knew what Jason meant about the intensity; I could see he was tired of thinking about it every day. But I didn’t believe he didn’t love it. That was impossible.

“He would kill me if I told him I wasn’t sure about it,” he said.

“Shut up. You’re sure.”

“It’s my whole life.”

“That’s why you’ll work harder, get better,” I said, sipping my Coke.

He sat up, took a deep breath. Dad was still at the center of the table, lecturing a couple of our teammates—always looking to the next game. “Sometimes I hate him for that,” Jason said quietly. Then he stood up and walked to the bathroom. I turned to watch his tall, skinny back recede into the dim lighting of the pizzeria.

See No Color

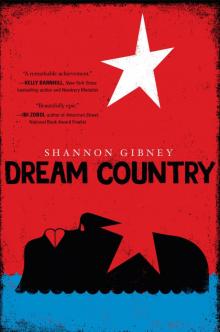

See No Color Dream Country

Dream Country