- Home

- Shannon Gibney

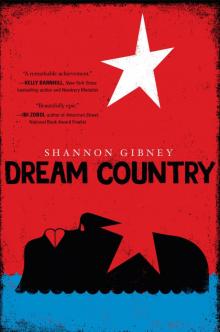

Dream Country Page 10

Dream Country Read online

Page 10

“Very few of the brutes make their way across the Nianda,” one man told him. “If you can get to the other side, you may find safety in Lofa.” He sucked his teeth and chomped down on a chicken foot from the pot of soup a bunch of them were sharing. “That far north, they don’t think it’s worth it-oh. To risk the rains and mosquitoes and beasts of the forest for their precious coins.”

Togar nodded, taking heed of their words. He was the first Bassa man from that far south that many of them had ever encountered, and they were as eager to compare stories of the local chiefs, paramount chiefs, and district commissioners.

“This Congo government only for the Congo people—everyone knows that. We country people just like the rice we grow for them: They eat it, eat it, eat, then shit us out,” a man said, and the rest of them laughed bitterly and nodded in agreement.

* * *

—

Later on, he saw a small, bright boy with straight hair and a thin nose like a crow helping his mother gather firewood. His color was somewhere between the strange, ghostlike hue of the Congo people, and the familiar deep black of the villagers. The man next to him noticed him staring, which made Togar want to stop, but he was somehow compelled. He had never seen anything like the boy, and wondered how he had come to be here, in this small Bassa village deep in the interior. Had his mother been raped by one of the Frontier Force bastards? Was this what they were trying to do to women like Fortee: breed out the blackness, the Bassa, through diluting it with their seed? Togar’s pulse raced at the thought.

“He is Henry, our half-caste,” the man next to him said. His tone was amiable, as if he were talking about one of his own children. The man nodded toward the boy and his mother. “His father was a Congo man who lived with us for a time, before he fell ill with the fever and died.” He shook his head. “A nasty, nasty business-oh. Left the mother and new baby out here on their own, to fend for themselves. The man had left his own people, said they were brutes who could not be reasoned with, and that one day all the violence they conjured on the land would come back for them. Said he didn’t want anything to do with them. And then he fell in love with our Monji, and ha!” The man clapped his hands and grinned. “That was it. He packed his things and left those Congo people, never to return.”

Togar looked at the man, perplexed. “This really happened?”

The man laughed again, and nodded vigorously. He pointed his chin in Henry’s direction. “Where do you think the boy came from-eh?”

Togar looked away. “I thought . . .”

“Ah, yes. That is what they all think at first,” said the man. “But if you had known George, you would have slowly come to the conclusion that he was a good man. As good as any in Tuma-La. Better than most, actually.” He thought for a moment. “Better than most. Told us once how the Congo people were so wicked to us because they had been unjustly treated back at their home, on the other side, and it had changed them in ways they couldn’t see. Made them angry, because they came to a place which was supposed to be their new home, only to find that it didn’t want them at all. The land didn’t want them. The insects and animals and plants didn’t want them.” He laughed. “And we surely didn’t want them-oh.”

Togar studied the man’s face to catch any traces of mirth. He didn’t seem to be joking, even though he had a jovial way about him. He tried to absorb what the man was saying: The Congo people had been hurt across the ocean, hurt so badly that they had to leave their home—a wound they would never recover from. It made sense as a story . . . but he was finding it very, very hard to accept as fact. The notion that these sheer brutes had feelings at all was impossible to him.

“George say, ‘We were slaves in our own home. So, we had to make someone else a slave in their home to feel like somebody,’” the man said. He looked back at Henry, laughing with his mother. “It was a strange story to hear, I admit it. But somehow, it made sense too, ya?” He looked back at Togar, for confirmation.

Togar nodded slowly. He watched Henry’s mother direct him to the bush, presumably to gather more firewood. The boy’s legs looked like small, delicate twigs themselves, as did his long, spindly arms. Togar wondered if he had inherited them from his Congo father, along with other traits that might weaken him in the bush. Everyone knew that Congo men—former slaves or not—could not survive the harsh life of the interior. Togar frowned and thought that his mother should have considered this before she lay down with a Congo man.

* * *

—

When it was finally time to leave the village, Manhtee and his wives insisted that he take a week’s rations. Another family in the village had an extra blanket and cutlass, which they also said he must carry. “You could be gone for months,” the man said, “and you will never survive with so few things.” Togar had to admit that they were right. It would still be at least fifty miles to Zigida, in the deep bush, quite possibly with militiamen chasing him. He would need every possible resource in order to arrive there safely.

As he stepped on the path that led out of the village, around Yela, and then past Palala, Togar felt a deep sadness that made him almost turn back. He felt even more alone than he had felt his whole time in the bush. Like his mother, father, brother, ancestors had left him to die on some strange land, among the beasts of the forest. Like he belonged to no one and would never find his way back home. He thought of Sundaygar then, and all he would endure in Giakpee with no father and no food or coin from the farm, and he willed the lump in his throat back down again. For you, I make this journey. With you, I am never alone. Togar turned back only one time to look at his new friends, and then set off again, letting go of the familiar comforts of human contact with each step into the wild, untamed bush.

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

TUMA-LA WAS CLOSER to Yela than Togar had realized, and it took him only a day to reach the bustling village. His friends had told him to stay out of the village proper, that soldiers had been spotted there recently, and that there were also informants who always had their eyes open for possible runaways. So, Togar went around the western side of the village, giving it as wide a berth as possible, skulking through the tall grasses and ironwood and mahogany trees. He made what he thought was halfway to Palala by nightfall, thankful that he had a real meal to fill his belly, and a warm blanket to fight off the chill. Now that he knew exactly where he was, he felt calmer and also more hopeful that he would make it to Lofa County. It was far, but others had walked farther alone in the bush; he had heard stories. He knew he could do it.

Togar drifted off to sleep, images of the rolling Wonegizi Range as Jorgbor had described it, flooding his mind. The thick green hills far off in the distance, touching the sky. The mist of morning covering one side. The sun burning it off quickly, so that the trees of the hills look like they bleed into one another. It is the most beautiful place you can imagine. Jorgbor would tell him these stories of her beloved Lofa, as they lay down together at night, Sundaygar dreaming contentedly beside them. He would ask her then why she ever left such a perfect place, and she would turn to him, her eyes shining, and say, Because it is not the only beautiful thing in the world, my husband. And then she would kiss him. And his hands would find their way to the small of her back, lingering there for just a moment before grabbing her buttocks as she softly moaned.

Someone was kicking him now. He felt an insistent boot nudging his ribs. Togar pried his eyes open, reluctantly leaving the warmth of the memory of Jorgbor and the promise of Lofa. The sour smell of alcohol woke him up with a start, as did a raucous laugh.

“That’s him all right,” someone said. “The beast in the village was not lying after all.”

The taut, unforgiving face of Commander Ross came into focus, standing in front of the soldiers who had almost raped Fortee.

Togar jumped back and grabbed his cutlass. He waved it at them, as he crouched and scanned the area for the possibility of escape. It was dawn

, and the sun was just beginning to cast shadows and light.

Ross laughed. “Don’t do something rash now, boy. So sorry to wake you from your dreaming, but we’ve just come to fetch what is rightfully ours. There doesn’t have to be any trouble about it.”

Togar backed up slowly, looking each soldier in their deadened, inebriated eyes. Although he had just woken up, they would be slower and clumsy. And there were only four of them this time.

“I understand your predicament, Togar,” said Ross.

Togar winced at the sound of his name, and Ross smiled.

“Yes, Togar Somah, husband of Jorgbor and father of Sundaygar,” he said. “I make it my business to know exactly who I’m dealing with, exactly where they’re going, and exactly what we may be able to offer each other.”

If he ran now, they would probably catch him and maybe maim him, and what of Jorgbor and Sundaygar? Togar’s mind couldn’t keep up.

And then a Bassa man stepped out of the stand of trees and tall grasses Togar was thinking about running to and shook his head. “It’s too late now,” he said, and he lifted a rifle.

Togar froze.

Ross laughed again. “Zigida is still miles and months away, through treacherous terrain, and hordes of insects that would delight to feast on flesh as young and succulent as yours. I’m sure you would contract malaria or some other jungle malady if you attempted to journey there so ill prepared. So, you see, we’re doing you a favor, returning you to Edina and Vice President Yancy’s rice plantation.”

“Traitors!” Togar blurted out, his frantic rage alighting on Manhtee and Tuma-La for a moment.

“Oh, I wouldn’t be too hard on them,” Ross said. “I really didn’t give them a choice, your friends. I said they could either tell me where you were, or I would round up all the small boys in the village and take them with us, as well. What would you have done?”

Before this moment, Togar did not know how deeply he could hate a human being, actually want to do a man physical harm. That he could take delight in it, even probably laugh while chopping up or pummeling his body. But that was what he wanted to do to Ross, more than anything in the world.

Ross sighed. “This is all well and good, conversing with you. We have a lot to catch up on, don’t we? All the time in this unbearable jungle, what rats you ate to stay alive, which magical heathen ceremonies you performed to keep yourself concealed for so long. I mean, I have to hand it to you: You really gave us a chase! You got the farthest that any country boy has. Isn’t that right, men?”

Looking bored and drunk, two of the men shrugged at Ross.

“This is quite an accomplishment for an ape man. You should be proud. But now it’s over. We have to be getting back to Edina. You have made us quite late, actually.” Ross nodded at the Bassa man.

The Bassa man made a move toward him, and Togar waved his cutlass toward him.

“Don’t,” the man said.

“You are even worse than the dung beetle,” Togar sneered at him. “Delivering your own people up to them for coin. I know your ancestors are disgusted, your family humiliated.”

The man stepped closer to him and raised the gun. “You don’t know me or my family-oh,” he said.

“Jaa se behn-indeh bun-wehnin,” Togar said. It was something his great-grandmother used to say: The truth needs no decoration.

“Dhu kpa sohn dyedeeh sin-in,” the Bassa man said. Togar winced at the meaning: A young child who sticks his hand in the flame is burnt. How appropriate for this tool of the white man to spit back their people’s wisdom, in order to enslave him.

Then the Bassa man knocked the cutlass out of Togar’s hand and tackled him. Togar pounded his fists into him with all his might as they both tumbled to the ground, but it was useless. The man was almost twice his size and flipped Togar over his head easily. Togar blinked slowly, the shock of landing on the ground and having the wind knocked out of him temporarily blinding him. Still, he could hear whoops of encouragement from Ross’s soldiers, who were finally roused from their boredom by this spectacle. The Bassa man lunged, intending to stomp on him. Togar rolled aside, dodging him easily as he landed awkwardly on the uneven ground. The man groaned and staggered as he tried to turn for another attack. Togar spotted his cutlass lying in the dust a few feet away from him and went for it. He grabbed its handle as the man charged at him again. Togar raised the blade as fast as he could, pointing it at his opponent. Then came the sick sound of metal penetrating flesh, and blood was everywhere. The man looked down at his stomach in horror and at the cutlass blade stuck halfway through him.

“You—you killed me,” he said, shocked. “You killed me, brother.”

Togar could only look on in shock, his hand still gripping the blade but shaking now. He had never killed or seriously wounded someone before. He hadn’t meant to do it; he was only defending himself.

“I’m sorry,” he whispered feebly.

The man pushed Togar’s hand off the blade and then fell back on to the ground. He writhed there for a little while, blood pooling in every direction, until he died.

Togar could not move, which made it very easy for Ross’s men to wrap his hands tightly in rope. Pee-nyuehn ni se hwio xwadaun. The phrase came to him then, for some reason, and he found he could not stop mumbling the proverb: “Pee-nyuehn ni se hwio xwadaun,” he said over and over again. Night must come to end the pleasures of the day. “It is night now,” he said finally. “It is night.” Then he collapsed.

Ross walked over to where Togar lay on the ground, his whole body scrunched together in the fetal position. Togar closed his eyes and tried to get back the feeling of kissing Jorgbor, the image of the Wonegizi Mountains, but they were gone.

“Oh, don’t be such a sore loser. You and I both know there was no way you would win anyway,” said Ross. “We own this country and always will. The people, the land, it’s all ours.” He leaned down so that he was mere inches from Togar. “You. Are ours.”

Togar refused to look at the brute.

Ross kicked him in the stomach.

Togar wheezed.

“Get up,” he said.

Togar curled up tighter.

“Now,” Ross said icily. “Need I remind you that we have complete access to your farm, as well as your wife and infant son? Don’t make me do things I don’t want to do.”

Togar sucked his teeth. Why, God? Must it be like this for the rest of my days? And I am a young man. He put the pain in his stomach out of his mind and stood up slowly.

Ross patted him on the back, and Togar flinched. “There now. You see how much easier things are when you can be reasonable?” He signaled to his men to gather their things and prepare for the long walk. “Our horses are stationed not far from here, but you of course will be pulled behind us. It will make the trip slower, of course, but far more meaningful, don’t you think?”

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

MUCH TO TOGAR’S SURPRISE, Ross walked beside him, seemingly delighted at the opportunity to make small talk with the man they had pursued through swamps and impenetrable jungle, and mud and overflowing creeks and riverbeds.

The bastard is not well, Togar thought. He is not sound. Perhaps this is what this work does to their minds. How it eats away their hearts.

“You really are an outstanding specimen,” Ross was saying. He reached out and clapped Togar’s shoulder, like they were comrades. “As is your brother-in-law, I might add. Do your families have any white blood in their lineages, I wonder? That would explain things. Your extraordinary abilities, I mean. Word is that Gardiah has been doing visionary work on the plantation. Thinking of crop rotations and soils and cycles we never would have considered. Positively striking, the mind of an ape holding that kind of knowledge and talent, don’t you think? I have half a mind to write my cousin in America, to ask him to book passage for such a monkey miracle to the next World’s Fair. The

journey might soften the blow after he hears what befell his bitch and their—oh, but where are my manners?”

Togar stopped and dropped to his knees.

“My condolences.” Then Ross yanked Togar to his feet by his shackles. “Anyway, I’m sure that the Western man would be shocked to see how far a coarse brute can come.” And on and on he chattered for miles until they came to their horses.

“Yes, Togar. I think I will send your brother-in-law to America,” concluded Ross as he slid into his saddle. “You, though.” Ross sucked his teeth and shook his head. “You poor black devil will surely end up on a boat to Fernando Pó.”

And they rode all the way to Edina over one week, Togar running behind them the whole way.

What our brethren could have been thinking about, who have left their native land and home and gone away to Africa, I am unable to say.

—David Walker

CHAPTER NINETEEN

1827, the Scott Plantation, 75 Miles from Norfolk, Virginia

“IF I AM GOING to die, it’s going to be my own kind of death,” Yasmine Wright said, standing up. Lani cooed in the red oak cradle James had carved for her. “It ain’t going to be no white man’s work killed me. It’s going to be God’s work.”

If there was no other way to leave, she would still leave. She had been tiptoeing around the Scotts all her life, and as she sat down on her bed to pull on James’s old boots, she delighted in the thought that she would stomp the entire fifty miles to Norfolk, thrashing through brush, kicking away burrs and pinecones. She would get on that boat, no doubt about it, and Little George, Nolan, Big George, and Lani would too.

She had been to Norfolk only once before, as a child, when Daddy was sick. There had been an outbreak of the yellow fever, and Old Master Scott (then Young Master Scott) had sent for the best doctor in the county. She was only eight at the time, but she had been sent to fetch Doc Lawrence, while the master himself sat over Daddy day and night, feeding him liquids and keeping a steady stream of cold cloths on his forehead until finally he slept. “I ain’t never seen no white man hang over one of us like that,” James told her on the carriage ride into town, which seemed interminable. She hushed him—even though he was ten years older—and he grimaced and turned away out into the night. She had known even then that she would marry him. She also knew that Daddy would die. Even if she and the family were set up with the nicest white man in six counties, their bodies were still broken by work and time.

See No Color

See No Color Dream Country

Dream Country