- Home

- Shannon Gibney

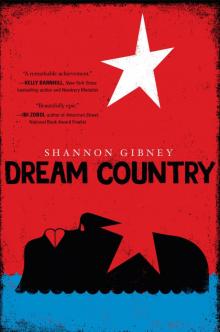

Dream Country Page 16

Dream Country Read online

Page 16

“Thank you,” she began, but the woman interrupted her again.

“Thank you for what? For showing you the way around hell?” She laughed, even more bitterly than before. “Thank you for being born black? For white folks who make sure you ain’t got nothing on two continents?”

Yasmine backed away from her, suddenly scared. Maybe this place had truly robbed the woman of her sanity.

The woman did not seem affected by Yasmine’s reaction. “You think the dry season’s bad? Wait till you see what comes next. Rain up to your ears, rain thrown down from the sky like bullets. Rain that will flood everything you built and ever tried to grow. Rain to bring water, water to bring the mosquitoes, and mosquitoes to bring death. I ain’t no root woman or savage devil-worshipper, but I can see fear well enough. And you got plenty, girl.”

Yasmine turned on her heel, giving the woman a halfhearted wave good-bye. She grimaced as she began walking away as fast as her legs could carry her.

“You want to thank me for something, thank me for reacquainting you with fear. That’s the onliest thing that’ll help you live here,” the woman shouted after her. It was remarkable, but no one else on the road even stopped to stare. “Stay away from hope,” she called. “That’s the surest path to death.”

* * *

—

When Yasmine got back to the communal house, she barely greeted the boys. It was all she could do to stumble through the door, hand Lani to Little George, and fall into a chair by the wall.

Big George regarded her curiously, through the corner of his eye. “You find anything good, Mama?”

She nodded absently, staring at the families gathered around her, some of them laughing, some of them resting, and most of them talking quietly with one another. It’s all the same to them, you know, whether we’re holding spears or Bibles. Black is black is black. Shaking her head, she hoped the woman’s words would fall out of her ears. But the more she stared at the newly arrived and clearly unprepared men, women, and children, the more she could see the truth of the woman’s words.

Turning away from his mother, Big George exchanged glances with Little George, who just shrugged and went on rocking his little sister in his arms.

The woman was right that this whole adventure had been masterminded by the whites, after all. Yasmine remembered the abolitionist meeting the Medgers had taken her to in Norfolk before they had left. A finely dressed speaker lectured to a full hall:

“Who are the members of this ‘benign’ American Colonization Society, anyway? Why, slaveholders, plantation owners, and those who benefit most from their cruel and devilish economy. They know only too well that the ranks of freedmen are swelling, and that the example of our lives only shows what they know in the deepest places of their black hearts, and what keeps them awake at night: that we are in every way equal men to them in skill, reason, and religion, and in fact, superior in our understanding and application of morality. They know that our brothers in bondage see this truth, as well—being equal to us in all parts save their freedom—and that their whole way of life should unravel were they to follow our similar paths. That is why they have embarked on this path of African colonization. It is not to provide us with better lives, and it is not to tame and bring the light of religion to our savage brothers and sisters across the Atlantic. No. It is only to eliminate what they view as their greatest threat to their livelihood. Us.”

CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE

“HOW I SUPPOSED TO clear if I ain’t got no plow, no ox?” Big George asked his mother one morning, the sweat from his brow dripping salt into his eyes. A cutlass dangled loosely from his palm, the remnants of freshly cut grasses and roots still on the blade.

The two older boys, who had worked in the fields back home, had similar responsibilities here. The only difference was there was no overseer to whip their hides, tell them to pick faster, move down the rows with more ease, or stop talking to each other. Yasmine clung to that distinction. Here in the motherland, they were in charge of their own destinies and their own field for the first time. And the children detested it.

They were in the middle of a massive slash-and-burn project, which would leave the ground charred and open. “This some savagery, Mama, working like this. It take us upward of a month to clear this whole area, and even then, we don’t know if the corn and greens gonna come up here,” said Little George. “This soil all wrong.”

The longing in his voice was as sharp as the hunger pains that wracked them at night. The meager rations of millet and dried herring that the colonization society agent had given them when they left the communal house were almost gone. When she had time to think about what they would do once it was gone, Yasmine was filled with terror. Nuts and greens would not fill their bellies.

“I wanna go back to Master Scott’s,” said Big George. He slumped down into the ground. “I miss Penny and hoecakes. I miss bacon, and I miss church.”

On the far edge of the field, Nolan played with a stick in the dirt, beside Lani. He was prancing around, yelling at her to pick up this imaginary pot, cut this onion, stir the stew. “Get to work, girl,” he shouted. Lani appeared to be happy to be included, and diligently did as she was told.

Suddenly Yasmine realized that Nolan was imagining he was back in Virginia, like everyone else. She blinked, trying to get her bearings, trying to remember how to be a good mother to her children. Even time itself was different here—she noticed that in the second it took her to blink, her entire adulthood stretched out in her mind. Jumping the broom with James, her mother’s shriek as she took her last breath and entered the kingdom of heaven, the agony of pushing each little body out of her. And then in the next instant, she was back. Back to a place where the sun was burning them to ash, back to her aching and impotent hands, back to freedom, and a four-acre plot of land that was made of clay and sand, but out of which was going to sprout plantains, beans, cassava, sweet potatoes, and American corn—even if she had to squeeze all the blood out of her body slowly to make them grow.

“Ain’t no going back,” Yasmine told them solemnly. She hoped they couldn’t see that she was telling herself at the same time, hoping that she would start to believe it soon. “We dead to Master Scott, we dead to Penny, dead to everyone back on that godforsaken plantation. And we gonna be dead soon ourselves, if we don’t get some of these seeds in the ground.” She struggled to get a hold of her words and the emotion behind them, to convey a sense of control to her children—a belief that they were in God’s hands now and that He had not forsaken any country or any people, no matter how remote. Build up the body of Christ, the preacher had said. And that was exactly what she intended to do. “Ain’t nothing here for us that we don’t make ourselves. That the price of freedom.”

Little George began to cry, which hadn’t happened since they left the other shore. It surprised both of them. For the most part, he appeared to be content in his new life, chasing chameleons and spying on colonists and heathens alike. Still, there was something soft in his gut; a dull ache for home that she worried would never leave him. “But we was more free back in Virginia—”

Before she even knew what she was doing, Yasmine reached up and slapped him. The sharp snap of it was as final as the sound of the whip on their bare backs, and it startled them all. But she could not let them venture down that road, not even a little. It was one thing to visit home in dreams and quite another to express that longing in waking life. It was dangerous: Before too long, the need to go back would consume the dreamer. None of them could afford that now. “Boy,” she said quietly. “Don’t never let me hear you say them words again.”

Little George gathered his knobby knees to his chest. He put his head on his knees and began rocking back and forth, sniffing. His big brother put his hand on his shoulder and glared at his mother.

You all can hate me, Yasmine thought, as long as we make it. They ain’t understand, but they ain’t have

to. God do. “Now get up offa them miserable behinds, and get back to clearing this field, both of you. I don’t care how it get done. Just see that it does. I wanna see our vegetables, from our field, in our new home steady growin’, get it?”

The two boys nodded, neither one meeting her glance.

Yasmine felt her stomach roll over, because she knew what she needed to do. She had been able to protect Nolan from fieldwork at Master Scott’s by making him Mrs. Barnes “special helper” in the kitchen. That was another dream she couldn’t afford now.

She strode over to the other side of the field, where he was humming quietly to himself, laughing at something Lani had just said. “Nolan,” she said, and her voice startled him. He jumped up quickly and brushed off his pants. She handed him her cutlass silently. He looked at her in confusion, clearly wanting to say something but deciding against it. The instrument weighed down his small six-year-old arm, and Yasmine’s hand flew to cover her mouth to contain a scream.

“Mama?” Lani asked cautiously. When Yasmine didn’t answer, she toddled over to her mother and held out her arms, her gesture to be picked up.

Yasmine’s eyes never left Nolan’s. “You got to work,” she said evenly.

Nolan blinked at her slowly, taking in the words.

“Go with your brothers,” she said, trying not to look at his soft brown palms. “You the only men here now, and you got to provide for us womenfolk.”

Nolan smiled at that, which made Yasmine smile, in turn. She thought that he would like that—he always wanted to think of himself as a Little Man, so helpful to his brothers and family.

“Mama!” Lani yelled, angry and impatient. She swatted Yasmine’s hip with both hands. Still, Yasmine ignored her. Something had changed between them of late, since Lani abruptly decided to stop nursing. Of all her children, Lani had nursed the longest, and the gentle but firm tug at her nipple had been a calming and steady fact of life these past two and a half years. Now there was only pain in her breasts. Still, Yasmine had to admit that she was ready to be done. She was exhausted and had nothing left to give the girl.

“Ain’t no men anywhere here, Mama? In the whole land?” Nolan asked, looking up from his cutlass. “What about the heathens? The ones by the woods outside of town? The ones took us ashore, when we first came?” He turned around and scanned the horizon, searching for a human figure hiding somewhere in the bush.

“No,” she told Nolan firmly. “They ain’t real men. They . . .” She struggled to find the words. “They heathens what don’t know right from wrong, reason from insanity. You the only man here. You and your brothers.”

Nolan looked shocked, but also proud. He puffed up his chest and gripped the cutlass handle with intention. “Well,” he said. “Let me get to helping.” And then he turned away from her and walked over to Little George and Big George, who were bent over, hacking the dry, dense brush.

“Mama, no!” Lani cried, tears streaming down her face now. Yasmine knew that in a few seconds, things would degenerate down into a full-blown tantrum. But right now, she was not interested in that. Right now, she wanted to watch her youngest boy walk away from her, his shoulders seeming to grow wider and more imposing with each step. She sighed. As Yasmine watched Nolan, she recognized her own self-determined gait in his, the way he walked on this new earth as if he owned it, and she was surprised to realize that it scared her.

CHAPTER THIRTY

IN THE END, it took even longer than Little George predicted to clear the field, in part because Yasmine spent the next three days in their shack, burning with fever. The children feared the African illness that had already claimed so many of the colonists, but Yasmine’s aching breasts told her otherwise. “I got milk sickness,” she told Big George. She pulled him close so she could see his eyes. “You and your brothers and sister got to keep working that field. You make this our land, you hear me?”

He did hear her. For three days, Big George led his siblings out to work their land while their mother sweated and dreamed.

Sometimes, the wildness called to her children, and she was powerless to pull them back to her. In her dreams, she could only watch.

Little George sat, watching men walk to and fro carrying wood or tools or munitions and the women gathered in the streets discussing domestic issues and trying to feel normal. He spied the shifting length of a chameleon tumbling down a tree branch off the side of the road. In a single motion, he was in the road, almost knocking over a man carrying two shotguns from the munitions locker and speeding into the bush. Lani, stumbled behind him, eager to keep up with her big brother.

“Be calm in your haste, boy,” the man called after him. “Else you gonna find yourself dead in the street before you grown!”

Little George spotted a small opening between the hanging vines of the mangrove tree that the chameleon was racing past and hid in it as quietly as possible. All the children knew chameleons were sensitive beasts, and the slightest rustle or sound could send them scurrying. Luckily Little George was light on his feet and could skillfully maneuver into spaces that his brothers could—or would—not. In a flash, Yasmine saw the secret he had told no one: his dream of becoming a great hunter in this country one day—perhaps the best that the colony had ever seen. He would hunt hippopotami, apes, even crocodiles, and would share all his spoils with everyone.

Little George lagged a slight distance, trying to spot the chameleon and anticipate its next move. “Stay here!” he hissed to Lani, who had finally caught up to him and was crouched beside him. She nodded vigorously, but Yasmine knew as well as Little George did that that did not necessarily mean she would do as she was told. Ah! This girl hardheaded! Yasmine would complain at least five times a day.

Little George was poised behind a towering fern and ready to spring into motion when he heard a rustling in the grass ahead. He froze and maintained his position. To be so close and come home empty-handed! He could not allow it. The chameleon was directly on the other side of the tree, he sensed. This was his chance! Little George pounced.

* * *

—

Darkness would come, and with it her children, dragging one another back from the field. Someone fed Yasmine liquids and kept a steady stream of cold cloths on her forehead until finally she slept soundly.

It was no chameleon’s tail Little George caught, but a hand. A black-black hand, attached to the arm of a girl about ten or eleven, her hair shorn to the scalp and various necklaces and shells hanging from her neck.

“Kuo!” Little George exclaimed.

He knew this creature!

The girl’s skirt had been whipped about in the tussle, and she turned away from him for a moment to fix it.

He took the hint and looked down. Just then, Lani came thrashing through the underbrush toward them. “Jo Jo!” she yelled.

“I’m here!” he yelled back.

The black-black child waved her right fist at him and turned to walk away, just as Lani reached them. She was triumphant, took her brother’s hand, and would not let go. “Black-black,” she said, pointing at the girl. “Black-black” had been Lani’s first words only a month or so earlier.

The girl looked from Little George to Lani and then held out her hands. Without hesitation, Lani took the girl’s hand, and in a moment George took the other. “Black-black,” Lani said again.

* * *

—

Fever held Yasmine tight through the next day. Again, she felt water on her lips and gagged at an offered bit of food, the smell of palm oil overwhelming and threatening to bring up her stomach. She heard sounds that had the timbre of soothing words, but she could make no sense of the words themselves. Soon she slept and dreamed again.

The black-black child led Lani and Little George deeper into the bush. They pushed through a curtain of trees and saw, curiously, a bright red door. They had finally found it!

“Humph,�

�� Little George said, and he had walked up to the door and knocked on it three times.

Lani still held the black-black child’s hand and bounced on the balls of her feet in anticipation.

The door flew open, and a short, middle-aged black woman with a small and worn piece of cloth wrapped around her stood before them. She had a kind face and warm eyes. She spoke as though to welcome the three children, and they seemed to understand, but Yasmine could not.

The woman stepped aside, and through the door they could see a clearing filled with huts made of what looked to be mud. Dried palm fronds served as roofs, and there were no doors. Women kneeled over fires, stirring soups and adding leaves and spices, while a group of men sat around talking and chewing kola nuts.

A small child, who looked like he had not only been playing in the dirt but eating it as well, ran up to Lani and began pulling at her leg. Lani screamed and tried to shake him off, without success.

The boy responded by jabbering something rapid in his language to Kuo, who responded with a series of harsh words that shut him up. The boy let go of Lani’s leg, which sent her stumbling to the ground. Then he frowned as if he were going to cry and turned back to Little George, opening his palms toward him in supplication.

Finally a woman who seemed to be a little younger than Yasmine looked up from the soup she was seasoning and shouted at the boy. Her cornrows shone in the sunlight, as did her black-black skin, which glistened with sweat. The suppleness of the natives’ skin was a subject that the Wrights had discussed on more than one occasion, as their skin and those of the other settlers seemed to be constantly drying and cracking. Little George wondered if they had a secret or if they were simply born that way in this land.

See No Color

See No Color Dream Country

Dream Country