- Home

- Shannon Gibney

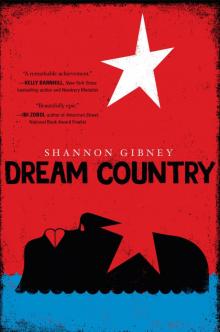

Dream Country Page 18

Dream Country Read online

Page 18

* * *

—

Years later, Nolan would recall how Yasmine often said it was during this period that her mind would not work right. She would be going along, tilling the fields, pulling cassava from the unyielding earth, and she would see a gecko on a tree branch or a monkey higher up near its top, and tell herself to remember to tell Little George when she got back to the cabin, because he was in the process of amassing a vast catalogue of all the vegetation and animal life in the area and could surely establish a vantage point from which to observe them here too. She would be constructing the whole conversation in her head, how she would say, The monkey’s fur was thicker and darker than those others we seen. Don’t know, but it coulda been another type. She would anticipate the way he would nod solemnly as he always did when he was thoroughly engrossed in a topic, Could be, Ma. Could be. It wasn’t until she had pulled the cassava root from the ground and was inspecting the leaves that her mind realized the conversation it was constructing could never happen, would never happen, because her son was dead now, had been dead for months, and would be forevermore. “My mind was broken then,” she would say. “Broken.”

CHAPTER THIRTY-THREE

1830, Monrovia, Liberia

TRY AS HE MIGHT, Big George could never quite get used to the rainy season the way his sister could. The rest of them would be hovering, shivering in the doorway of the tiny cabin, as the water pummeled the roof and trees and turned the ground to mud; and Lani would be out there right in the middle of it, dancing to some song only she could hear, sticking her tongue out to catch drops. George found the way that the rain bombarded them, in sheets of periodic swells of torrential downpour that came at the oddest moments, and then cleared for a moment before resuming—or, alternately, the ongoing slam of water that seemed to go on forever, flooding the streets and waterways for months on end—to be insulting. He couldn’t help but take it personally, the essential wrongness of the way that the thing known as rain was delivered in Africa. Rain was supposed to be manageable, to come in storms that visited occasionally and then left. It was not supposed to last for weeks on end, and it was not supposed to appear out of nowhere and overtake a land and the people who were trying to tame it. And it certainly was not supposed to interfere with the normal daily work of farming, tending to the animals and general life of the colony. And yet, every May to October, that is exactly what happened. They were confined to the small space of the cabin for days and weeks, watching the dull theater of rain and the wind that carried it whip palm fronds and tree branches to and fro, and the fields devolve into a pond for mosquitoes to gather and breed in. Big George found it downright offensive, the rainy season in this country, and because of this felt the need to challenge it whenever he could. Succumbing to its force seemed weak to him and the opposite of what they had come here to do. Which was why he jumped at the chance to join the expedition that Gov was leading into the bush.

“It ain’t a good idea,” Yasmine told him one night, before the dying embers of a small fire they stoked in the cabin. Nolan and Lani lay splayed out on the ground beside them, unconscious and snoring blissfully in that way that only children can, free of the burdens of men. “There a reason the savages don’t do nothing in this weather.”

Big George sucked the last marrow from the bones of a slim goat they had killed a few days before. “Yeah,” he said. “They be lazy.”

Yasmine licked a few specks of yam from her fingers. “No, that ain’t what I mean.” She wiped her hands on her apron and cleared her throat. “They understand something about this land and the way it be that we can’t really. They not out in the rain ’cause they seen what the rain can do, and they respect that. Plus, they know the season of sun’s comin’ soon enough.” She tapped her son’s arm lightly, almost playfully.

After Little George had gone, it seemed to Big George that Yasmine had softened somewhat toward him and his siblings, like she had decided to enjoy her remaining children, not just fear for them all the time. “Seem like we the onliest ones can’t accept the way things be here. Always tryna make everything like it was somewhere else.” She shook her head. “That’s why we ain’t hardly got no crops.”

Big George threw his goat bones aimlessly out the small window beside them. A modest pile of bones and scraps from meals past was growing there. “You the last person I’da thunk would say we got something to learn from them criminals.”

Yasmine winced. “I ain’t saying—”

Big George looked his mother right in the eyes. “But you is, Ma.”

Yasmine frowned and looked away. “I worry I done wrong, bringing you here,” she said. “I worry that this place making you—making us—different. Meaner. Smaller, somehow.”

It was the truest thing she had said to him in months, but it was like Big George hadn’t heard her at all. “Look,” he said, “Gov say they planning something. Another raid on the munitions locker maybe, a direct attack on the colony, maybe. Bassa men been trading with the Kru been trading with the British for guns and ammo and powder and knives and God knows what else.”

Yasmine sucked her teeth. “Watch your tongue, boy.”

Big George shook off her admonition as he would a fly and continued his analysis. “Slave trade may be illegal, but you and I both know as long as it make money, they always be demand for more captives to steal and take back on them there ships. Now, I ain’t fixin’ to let that happen to me and mines, after all we been through.”

The children stirred beside them. Nolan swung at an invisible mosquito.

Big George took his mother’s hand and gently guided her glance back to his. “They comin’ for us, Mama. One way or another. You can be sure of that. They not just sitting there in the rain, eating they goat meat and yam like sitting ducks. Naw. They preparing an army to get rid of us, wipe us out. Gov sent out scouts three days back, and they came back, reported that they seen them savages getting they guns and spears ready for something big, looked like.”

Lani stirred and mumbled in her sleep. Yasmine put a finger to her lips and glared at George. They were quiet for a moment.

“How you know it us they comin’ for?” Yasmine hissed. “Just as likely they comin’ for them Kpelle or Gio. Or maybe they finally ready to deal with them Kru and Mandingo they hate so much. You don’t know.”

He squeezed her hand and prayed for the words to soothe his frail mother’s heart. He had been dreading telling her, but now there was no way around it. He had waited too long; they were leaving tonight. “Gov always know, Ma. Always.” He took a deep breath. “That’s why I going with him tonight. We gotta surprise ’em, ’fore they come for us.”

Yasmine blinked and was quiet for a moment. “You ain’t going,” she said as evenly as possible. “You ain’t.”

Big George gathered his gun from its standing place in the corner, as well as his pouch of supplies, ammo, and powder. “I prayed, Mama,” he said. “I asked Him to protect me, protect us.” He looked down at her, her whole body taut on the floor where they had been sitting. Big George smiled. “He told me I was righteous. That I would win.”

She shook her head. “God don’t—”

He silenced her by picking her up in a huge embrace. “He say I gonna win,” he said. Then louder: “He say I gonna win, Mama!”

* * *

—

Gov’s expedition did win; Big George had been right. The group of five men had indeed located the same Bassa faction that caused so much trouble so many months before, engaged in a plot with some men from a Dei village to not only raid the colony’s munitions locker, but to then use its weapons to capture as many of the colonists as possible.

Almost three full days after Big George left the small cabin and ventured into the muddy, wet world outside it with the expedition, they marched back into the colony, bloodied, weary, but victorious. Because they acted swiftly, the colonists had had the element of surprise a

nd were able to come at the insurgents while they slept. Each man told how he had killed one, two, even three of the savages while they slept, unaware—except for Big George, who through his cunning, strength, and superior fighting skills, had been able to kill seven. “We never would have been able to overpower them without him,” the governor told Yasmine gravely, as the rain hammered both their skins to numbness. “He was truly a patriot. A hero. You should be very proud.” He clasped a massive, scarred hand on her shoulder. He brought her beside a tree with leaves enough to partially shelter them and told her that Big George had fallen at the river. After suffering so many losses at George’s hand, the savages’ leader—known to be an exceptionally skilled warrior in villages throughout the area—chased George out of their encampment, pursuing him for miles until he cornered him by the bank of the river. “None of us were there, so we don’t know exactly what happened,” Gov told a weeping Yasmine. “We only saw . . . after.”

Lani, who loved the rain and had never seen her mother cry, came out of the cabin and carefully took her hand.

The governor tried to embrace Yasmine, but she stepped away from him before he could manage it.

“What did you see?” she whispered.

The rain seemed endless. It pounded his pale face and bulbous features, making him look even more distasteful than she found him. Lani held on tighter, the harder the rain fell.

The governor shook his head. “We saw . . . his body . . .”

Yasmine found her voice again. “Tell me what you seen, exactly.”

The man looked at her, still not fully grasping her words. “Your son’s dead, ma’am. That’s what we saw.” He reached out to her again, but she took another step back.

She stared back at him. “I need you to describe him. How he looked. What they done to him. Where he is now.”

He recoiled visibly. “But you can’t want to know—”

“But I do,” she said. “I do.”

Lani looked up through the rain at her mother’s face, which seemed very old suddenly.

The governor scowled. “There’s no reason—”

“He’s my son,” Yasmine said, emotionless. “What you done with him?”

He shook his head. “Ma’am, I see you’re upset. Hell, who wouldn’t be? The savages done killed your eldest boy. One of the kindest, most devoted, best fighters we got in the whole colony. There’s none like Big George. Never will be again. That’s God’s truth.”

He looked like a thick, tired tree that the wind could upend if it blew hard enough. Yasmine wished it would. She really wished it would.

“They sever his head from his body? They cut him into bits with a cutlass?”

The governor shook his head again. “What kind of . . . ?” Then he pointed at Lani. “With your little daughter here too, you want to talk like this? Yeah, I been warned about you. Plenty of people say you ain’t no natural woman. Being so close to George, I always defended you. But now I can see they were on to something.” He tapped his head. “Something maybe ain’t quite right up there in that head of yours. Yeah, I’m real sorry for your loss. Real, real sorry, in fact. George was my best friend, my best man here at the colony. Gonna miss him something fierce, myself. But he died defending those he loved. Can’t you find a way to take some solace in that, at least?”

“Shut up!” Yasmine screamed, dropping Lani’s hand so she could cover her own eyes. “Shut up! Shut up! Shut up!” Lani felt her mother completely lose control of herself. Her boys were dead. Dead. Dead. Dead. Dead. Dead. Dead. Dead. Dead. Rotting in the ground. Never coming back.

People were running toward them now, gathering by the commotion. Lani tried to hug her desperately. “I need to see the body,” Yasmine told the governor when she opened her eyes again. Her tone was even, emotionless again. “Where the body?” She took a step toward him.

The governor took a step away from Yasmine and Lani. Something in his eyes—Lani saw it was fear—let her know there was more to the story. “He isn’t . . .” He shook his head.

“What?” she screamed, again losing her composure.

He jumped, this man, this great general of the colony, at the sound.

Lani finally succeeded and encircled her tiny arms as far around Yasmine as they would go.

“The savage cut him up and fed all the pieces down the river,” said the governor. “The only thing he left was the head, so we knew it was him.”

Lani felt for a moment that her mother was becoming the rain itself, the water collecting everywhere around her, flooding her pores and blinding her eyes. Yasmine could gather herself with force and slam into an object to break it, as she had seen water do even to stone. But she could also dissolve. She could let herself disappear, become another drop of water entirely, assume its weight, its consistency, its route. Yasmine fell down then. Down into the mud. And even though her mother still had Nolan and her, Lani saw in Yasmine’s eyes the desire not just to die but to be annihilated. To cease to exist, to think, to remember anymore. For everything that was Yasmine Wright to wander away from itself and find another form to take. It would be better to be a log or a rock in a river, slowly whittled away by the steady current of water. Far, far better.

CHAPTER THIRTY-FOUR

1845, Monrovia, Liberia

DUSK WAS ROLLING IN on what Lani supposed was the longest day of her life. The clouds thinned across the horizon, and the sky was turning a shade of blue that reminded her of the large vats of indigo some of the women in the village stirred with long sticks slowly, waiting for it to gain strength enough to hold color on fabric. The breeze from the ocean had become cooler now, urging her to pull her shawl tighter across her narrow shoulders. She scanned the path to town for any trace of Gartee, but could see nothing yet. Her right foot tapped against the ground nervously, a habit her mother was fond of telling her was both annoying and unladylike. Lani smiled at the thought: quite a charge from the woman known across all quarters of the colony as Mr. Wright. Her mother, head of the most prosperous farms in Monrovia, second to Governor Whitman, and ace marksman in the troops, would seem on the surface to put no stock in common notions of ladylike behavior. But Yasmine Wright was nothing if not complicated. Lani sighed. For once, she wished she didn’t know this so well; it would be easier to go on like they had been and pretend that what was happening was not.

Finally the sound of footfalls on the grasses came closer and closer. Lani sat up—he had finally returned from the village with news from the elders. They would finally set a date and finally be free from all this sneaking around. But as the footsteps neared, she realized that they were too deliberate, too heavy to be Gartee’s, who like so many Bassa men, walked like his feet and the ground were two halves of the same whole. Nolan, on the other hand, walked like he owned the place. Now a successful trader, interpreter, and negotiator who was widely favored to be the governor’s successor, he effectively did own it.

“Good evening, Sister,” Nolan called across the path to her. He had come from a lengthy set of talks with a Grebo paramount chief, who presided in a district a week’s walk from Monrovia. He and the governor’s people were attempting to obtain more land for the settlement, as well as trade in various goods.

“Good evening,” Lani said evenly, once her brother had reached her. “How the journey?”

He sat down heavily on the rock beside her, throwing his suitcase into the dust. Normally he would insist on sitting on a proper chair inside and having one of the small girls or boys bring him water, rice, and soup immediately after such a long journey. But it wasn’t often that he found his sister alone and unoccupied like this, and he wanted to talk to her.

“Fine,” he said, wiping his brow with a handkerchief. This damned country was so humid, a man had barely bathed before he found himself drenched in sweat and dirt again. “We got half the land for the settlement. I think the chief can see reason in it. I think it won

’t be long before he gives us the rest, either.”

Lani laughed. “Who wouldn’t see reason, when reason got rifles and spears and friends from every ship comes to port from America and Europe behind ’em?”

Nolan frowned and made himself laugh. His baby sister had always been contrary growing up—favoring salt over sugar, pepper soup over the American chicken soup their mother labored over for so many hours. But he had assumed she would grow out of it, like so many other young girls, as she came closer to womanhood. She hadn’t.

“What you doin’ out here, anyway?” he asked, thinking it best to change the subject. A mosquito buzzed in front of his eye, and he swatted it away. “You gonna get eaten alive.”

Lani shrugged. The mosquitoes never bothered her as they bothered Nolan and their mother. Sure, she got bitten but never like they did, and by some miracle she had never come down with the fever. “Beautiful night. Thought I’d take in some air.”

He nodded. Their mother probably wanted her to visit with her in the sitting room, but her contrary daughter had declined. Those two were always at each other’s throats lately.

They sat there for a moment, he catching his breath from the long trip, she peering intently at something in the distance. Nolan followed her gaze and saw something maybe a half mile away from them making its way toward them. It was small and black, but moving swiftly across the terrain. He sighed. He should have known.

“Why do you hang on him so? You know nothing good can come of it,” he said in a small voice. “You know Mama ain’t never gonna allow whatever it is you two dreamin’ of.”

Gartee had come to them from his village when he was five, to help out with the fetching of water, cleaning and maintenance of the house, caring of the livestock. It was rapidly becoming the custom here to have at least one small boy and small girl from the bush come and stay in your house and help out, in exchange for providing them with the gifts of civilization: education and the Word of the Lord. Not to mention regular meals and a decent roof over their heads. Nolan was of the same mind as most of his fellow Congo people—the name the local tribal men had given them: The natives were getting the far better deal in the arrangement.

See No Color

See No Color Dream Country

Dream Country