- Home

- Shannon Gibney

Dream Country Page 24

Dream Country Read online

Page 24

—Shannon Gibney

Minneapolis, Minnesota 2018

SELECTED FURTHER READING

Clegg, Claude Andrew. The Price of Liberty: African Americans and the Making of Liberia. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

Cooper, Helene. The House at Sugar Beach: In Search of a Lost African Childhood. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2009.

Gbowee, Leymah. Mighty Be Our Powers: How Sisterhood, Prayer, and Sex Changed a Nation at War. New York: Beast Books, 2011.

Hartman, Saidiya V. Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007.

Johnson, Charles Spurgeon. Bitter Canaan: The Story of the Negro Republic. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1987.

Shaw, Elma. Redemption Road: The Quest for Peace and Justice in Liberia. Monrovia: Cotton Tree Press, 2008.

Walker, David, and Peter P. Hinks. David Walker’s Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World. University Park: Pennsylvania State Univ. Press, 2000.

Wiley, Bell Irvin, ed. Slaves No More: Letters from Liberia, 1833–1869. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1980.

Wilkerson, Isabel. The Warmth of Other Suns: The Story of America’s Epic Migration. New York: Vintage Books, 2011.

SELECTED VIDEO

Firestone and the Warlord. PBS Frontline, 2014.

Liberia: America’s Stepchild. Grain Coast Productions, 2002.

Pray the Devil Back to Hell. Balcony Releasing, 2008.

A SELECTED TIMELINE OF MAJOR EVENTS IN LIBERIAN HISTORY

1816—The American Colonization Society (ACS) is founded in Washington D.C. Present at the founding meeting are future presidents James Monroe and Andrew Jackson, The Star-Spangled Banner author Francis Scott Key, two future secretaries of state, and the nephew of President George Washington.

1822—The ACS works with freed slaves and free blacks to organize their return to Africa. After landing in Cape Mesurado, the initial group of colonists names their first settlement Monrovia, in honor of President James Monroe.

1824—Colonists decide to call their new country Liberia.

1847—Using the United States Constitution as a model, colonists create a constitution for Liberia, thus making it the only independent state on the African continent at the time. More than ten thousand colonists reside there.

1897–1930—Known as “the Forced Labor Period,” this era in Liberia is marked by government officials colluding with the military and American and European business interests to recruit indigenous “boys” for labor—by any means necessary. Many of these de facto slaves are sent to plantations on Fernando Pó, the European name for Bioko, an island off the coast of West Africa.

1971—William Tolbert, Jr., becomes president of Liberia, after the death of President William Tubman. Like every other Liberian president up to this time, he is Americo-Liberian, or a descendant of the colonists.

1980—Following a year of protests by various activists and political groups, Tolbert is assassinated during a military coup organized by Master Sergeant Samuel Doe. Only four members of Tolbert’s cabinet escape execution in the days that follow. Doe’s faction suspends the constitution and assumes control.

1985—Mired in allegations of voter fraud, Doe wins the presidential election.

1989—Charles Taylor and the National Patriotic Front of Liberia (NPFL) start rebellions that further destabilize the country and lead to civil war.

1989–1996—The First Liberian Civil War, in which more than 200,000 Liberians lose their lives and more than a million others become refugees. The war is notable for the involvement of child soldiers, many of whom are led by the notorious warlord, Joshua Milton Blahyi, known as General Butt Naked.

1990—The United Nations High Commission on Refugees opens the Gomoa Buduburam Refugee Camp, near Accra, Ghana. More than twelve thousand Liberian refugees seek safety there.

1997—In a climate of widespread voter intimidation, Charles Taylor is elected president.

1999–2003—The Second Liberian Civil War, in which rebel groups attempt to overthrow Charles Taylor’s government. More than 250,000 are killed between both civil wars.

2006—Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, one of the four who survived the Tolbert coup in 1986, is elected president of Liberia and begins the long and ongoing process of rebuilding the postwar nation. She is the first woman president in Africa.

2017—George Weah is elected president. It is the first democratic transfer of power in Liberia since 1944.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Although writing is an activity that takes place in a solitary room with a solitary human, the truth is that all novels are the collective work of many individuals, institutions, communities, and resources, over many years. Dream Country is not only not exceptional in this way, but is actually an outlier in that it took the extraordinary effort and support of numerous people and organizations, over a period of twenty years to bring it to fruition. This is no small feat, and I am so grateful to everyone for their contributions.

To Carnegie Mellon University, and the Alumni Study/Travel Award stewards who saw fit to give a wide-eyed twenty-two-year-old graduate a fellowship to travel to Ghana for a year to study relationships between continental Africans and African Americans and write short stories on this very broad topic so many years ago, thank you. The seeds of that journey are what grew into this book.

Thanks also to the McKnight Foundation and the Loft Literary Center, whose generous funding made possible the time and space needed to complete key portions of the manuscript.

To my parents, Jim and Sue Gibney, who stood behind me and helped me plan and execute every trip and process every return, and who have never faltered in their support of their daughter’s strange writing vocation and wanderlust, your constancy and love are the rock that has always steadied me.

Candid interviews with Samuel Brown in South Dakota and Clarence Nah in Monrovia gave me a deeper understanding of the experiences—and therefore the psychology—of young men like Kollie. Thank you for the immense gift of trusting me with your stories.

Books, including Claude Clegg’s The Price of Liberty: African Americans and the Making of Liberia; Bell Irvin Wiley’s Slaves No More: Letters from Liberia, 1833–1869; and Charles Johnson’s Bitter Canaan: The Story of the Negro Republic, provided essential historical background for the second, third, and fourth parts of the novel.

Sensitivity readers Joy Dolo Anfinson and Nyemadi Dunbar offered much needed objective eyes to the manuscript at a key time in its development. Thank you so much.

Thanks also to Jon and Megan for being an exceptional uncle and aunt to my children, so I could work.

Thanks to my badass agent, Tina Dubois, for fighting for me and the manuscript. You have made me a believer in the odd world of agents—something I never thought I’d be able to say.

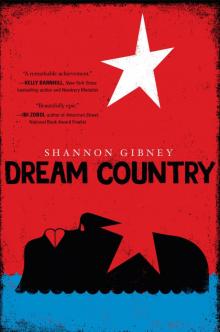

Thanks to everyone at Dutton and Penguin Young Readers—Julie Strauss-Gabel, Anna Booth, Melissa Faulner, Natalie Vielkind, Anne Heausler, Rosanne Lauer, Katie Quinn, Lindsey Andrews, Kelley Brady, and Deborah Kaplan—for being so amazing and invested in Dream Country, from impeccable copyediting, to visionary designing, and everything in between.

Thank you to Edel Rodriguez for his transcendent jacket illustration.

Thank you to Chaun Webster for creating a brilliant discussion guide.

Thanks to Bobbi Chase Wilding, Dagny Hanner, and Karen Hausdoerffer, for hanging in there with me all this time, and to the V-Vault Ladies Taiyon Coleman, Kathleen DeVore, Shalini Gupta, and Valerie Deus for getting me through a very rocky two years.

Greta Palm, Lori Young-Williams, Bao Phi, Sun Yung Shin, Juliana Hu Pegues, Sarah Park Dahlen, Ben Gibney, and so many others, know how much I appreciate how you hold me up when it’s called for, and throw down when necessary.

Boisey and Marwein, you didn’t hav

e a choice, but all the time you gave up with Mama for this manuscript meant so much, and will one day be paid back in full. I promise.

Andrew Karre, we have done it once again: Created a book out of thin air, it seems. Your care, professionalism, vision, and commitment to excellence pulled the best version of Dream Country possible from my consciousness, into the editorial process, and now into the world. I could not imagine a better editor. Thank you, a million times, thank you.

DREAM COUNTRY DISCUSSION GUIDE

Ruptures

“For me, the rupture was the story.”

—Saidiya Hartman, Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route

“Then he came back out on the porch and sat there for hours, watching the sun rise. Wondering if his own history was just a dream-loop folding back on itself over and over again, in endless variation and repetition, always in search of a place to rest.”

—Dream Country (this page)

Dream Country weaves together several stories and repeatedly confronts the trauma of enslavement, colonialism, and war on two continents. The resulting narrative tapestry is not linear and is frequently and violently ruptured. In many ways, the author refuses to allow the story “a place to rest,” perhaps due in part to how these difficult historical traumas lay right beneath the surface for Kollie and Ujay, Fanewu and Angel, Eddie and Clark.

In what ways does the author “rupture” the story and attempt to recover histories in this book?

From the beginning of the book, we see various examples of a hostility living right beneath the surface of almost every interaction between African Americans and Liberians. Discuss what reasons you see for this.

Education comes up often in this novel, both as a primary instrument for carving the way “out” of global second-class citizenship and also as a site of violence. How is education experienced by Angel? Kollie? Clark?

There is a very difficult scene in the book’s beginning where Kollie witnesses the school security guard, Eddie, assault Clark. In that moment, Kollie feels stuck and unable to interrupt the violence. After Eddie leaves Clark, Kollie attempts to comfort him but fails, and Clark, in a fragile state, threatens Kollie, demanding that he never say anything about the incident. Discuss what connections these kinds of violent experiences have to silence. Why do you think, in this moment, Kollie and Clark were unable to find a way to be tender with and comfort each other? Do you see parallel moments elsewhere in the book in other places and times?

Throughout Dream Country, Ujay is hardened to Fanewu, Angel, and Kollie. Why do you think this family was so distant from one another?

Part III tells the story of Yasmine Wright and her family, beginning on an early nineteenth-century plantation in Virginia. Yasmine, like many enslaved, formerly enslaved, and other “free” black people in North America, looks for a better life for herself and her children, one where they will not always have to go through the back door. Describe the role that the American Colonization Society (ACS) played in many African Americans departure to “settle” Liberia. How did this create a rupture between African Americans and indigenous Liberians and reproduce the master-and-enslaved that the Wrights fled in Virginia?

Yasmine begins Part III as an unambiguously black woman, but by the end of her story, Lani, Yasmine’s youngest child, is described by an indigenous Liberian as “unabashedly sweet white woman.” Discuss how the book presents “whiteness” and “blackness.” What causes a person to be perceived as “white” or “black” in each of the sections?

Discuss the American Colonization Society’s interpretation and practice of Christianity. Did this interpretation view the indigenous people of what would be Liberia as fully human? Did Yasmine adopt the same view of Liberians? How does Yasmine’s character develop in her view of the indigenous people of Liberia in practice over time?

Dreams

“We are the ones on the plantation speaking and singing to each other in code, to let others know our intent—such art and artfulness precede what sets us free, and more often than not, are the code by which that freedom is achieved. If we cannot first imagine freedom, we cannot achieve it. Freedom, like fiction and all art, is a process in which the dream of freedom is only the first part.”

—Kevin Young, The Grey Album: On the Blackness of Blackness

“ . . . I have imagined in some shadowy part of my mind and heart that my father lost someone close to him, someone he loved deeply, and in doing so, lost his own dream too. Which is why he is so intent on the rest of us letting go of ours before they really start. At least now I know that he believes these losses are a kindness.”

—Dream Country (this page)

This novel is aptly titled Dream Country, as it is a mosaic of stories highlighting self-recreation and intense longing for elsewhere. This elsewhere is an imagined territory—a dream—that is sometimes spoken of, other times kept hidden away, safe from war or the auction block. Wherever the dream lives, the fact remains: “if we cannot first imagine freedom, we cannot achieve it.”

Take a moment to think about the various hope and dreams parents in this novel have for their children. Discuss the ways these worked out or didn’t and why.

Dream Country moves backward and forward again and again. Why do you think the author chose to structure the novel in this way?

In Part II of the book, Togar remembers in a dream his young wife explaining why she left the home she loved to live with him in his village: “Because it is not the only beautiful thing in the world, my husband.” This line is implicitly echoed again by Felicia, Angel’s fiancée, when she answers Angel’s question about why she left Chicago. Discuss the ways that dreams of love help characters throughout the book overcome, if only momentarily, the ruptures in their lives.

At the end of the book, Angel writes about her father, saying that she believed “he lost someone close to him, someone he loved deeply, and in doing so lost his own dream too. Which is why he is so intent on the rest of us letting go of ours before they really start.” Discuss how the dashed dreams of parents can become unfair expectations or imposed life-paths for their children.

The book’s title is Dream Country, and the characters in the novel cling to imagined or dreamlike territories in their minds: Yasmine of an Africa free of the ghosts of slavery, Ujay of a liberated Liberia and then later of any place free of all the terrors of the Liberian civil war, Kollie of his club in the suburbs. In what ways do these imagined territories weave together? In what ways do they collide?

Angel at the end of the novel, seems to be the fulfillment of many of the various dreams. In the closing paragraphs she speaks of how, “Our bodies enclose the twisted threads of history—passed flesh to flesh, from parent to child, conqueror to conquered, love to beloved.” Discuss the twisted threads in this books five generations. How do they come to culminate in Angel?

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Shannon Gibney is an author and university professor. Her novel See No Color, drawn from her life as a transracial adoptee, won the Minnesota Book Award and was hailed by Kirkus as "an exceptionally accomplished debut" and by Publishers Weekly as "an unflinching look at the complexities of racial identity." Her essay "Fear of a Black Mother" appears in the anthology A Good Time for the Truth. She lives with her two Liberian-American children in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

www.shannongibney.com and @gibneyshannon

What’s next on

your reading list?

Discover your next

great read!

* * *

Get personalized book picks and up-to-date news about this author.

Sign up now.

reading books on Archive.

See No Color

See No Color Dream Country

Dream Country