- Home

- Shannon Gibney

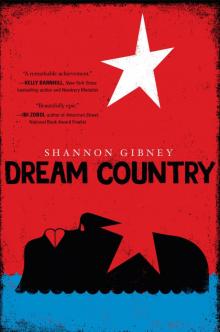

Dream Country Page 4

Dream Country Read online

Page 4

“Okay!” X clapped his hands, startling Kollie out of his reverie. “Let’s run it again. Except this time, Gabe, you switch with Vince and make a run up on the left. Watch how Vince defends you. Kollie, you go center.”

It was an unseasonably cool October day, and the wind was at Kollie’s back, pushing him forward as he found the ball at his feet. He didn’t really remember X starting the drill, but soccer was like music: Finding the flow was effortless. He moved the ball forward, running and tapping with the tips of his shoes. Sometimes it felt almost like he was dancing, he and the ball, each one taking its cue from the other, spinning in or out of control endlessly downfield. This was why he played, for this feeling. He would never be tired, would never have to stop or think. It was pure freedom, and therefore so fleeting that he could not even describe it.

In the bleachers, both Angel and Lovie sat waiting for Kollie to finish practice. Books on their laps, they were separated by several rows, but they both wanted something from him.

On the field Kollie deftly pulled the ball backward as Gabe came sliding in to try to gain possession. Someone called for Kollie to pass as he spun away from another defender. No one was taking this from him.

The first frost had not come yet, so the ground was still soft. Kollie felt his cleats bite as he changed direction and juked another defender. This was not part of X’s drill. He could do whatever he wanted now, and the goalposts were becoming larger and larger in his view.

X clapped his padded goalkeeper gloves together and then crouched down, elbows on his knees. He looked straight at Kollie. Kollie grinned. This was what he’d wanted.

But the angle he’d taken on his run downfield had been slightly off—and X had positioned himself accordingly. Kollie was too far left—his weaker foot—and since he’d chosen to go one-on-one and ignored all the cries to pass, no one had bothered to get in position to receive a cross or even a back pass.

Kollie managed to beat one more defender before he was forced into a weak, left-foot shot X easily saved while managing to give him a disappointed look at the same time.

CHAPTER SEVEN

AT DINNER THAT NIGHT, Kollie picked at his fish and rice. His mother sat across from him at their modest kitchen table, almost inhaling the food she had cooked the weekend before. After working a double shift at the hospital, she had raced to St. Mary’s to take a biochemistry test. She was only three classes and a board exam away from her RN degree. Most of this was noise to Kollie, who just knew that she was always working. His mother eyed him wearily. “How was school today?”

Kollie sighed. He wished she knew how much he wanted to be the son she could rely on, not the one she had to worry about constantly after making herself sick through too much work. He wished he could tell her something good. “It fine-oh,” he said softly, chewing his meat.

The garish clock his parents had purchased in the dollar store ticked in the silence between them, but did not fill it. Angel was at a yearbook meeting, and his father was working late (they all knew he was at Vivian’s place, but “working late” was what they always said), so it was only the two of them.

His mother glanced at his barely touched dinner. “You want something else? Or you just not hungry-menh?”

When he had first come to America, all he had ever wanted to eat was soup and rice like every other Liberian he knew, but in the past few years his palate had become decidedly more American and he preferred a hamburger and fries to a bowl of torbogee any night. But that wasn’t why he wasn’t eating now. He had actually lost his appetite. “I fine-oh,” he said.

If his mother didn’t believe him, she didn’t let on. She shrugged and scooped up the last few bites on her plate. “A boy need to eat-oh.” Her blue hospital scrubs clung too tightly to her stomach, which was becoming thicker rapidly, it seemed to him. In Africa, fatness was seen as a sign of prosperity and even status, but here you were thought to be lazy or even a bad person if you were big. He knew she ate because she was sad, and also lonely. A devout Baptist, it was the one vice she allowed herself.

“I ate at school,” he said, seeing the image of the lunch his mother had meticulously prepared for him poured into the garbage. Then he stood up and grabbed his plate. The dishes from the last few days were stacked in the kitchen sink, almost overflowing onto the counter. If he couldn’t be the son she needed, then the least he could do was the dishes. He began to run the water, then grabbed the scrubber. His father would have laughed at him for doing women’s work if he were there. But he was not there.

“Eh-menh, I almost forgot!” his mother exclaimed suddenly. She sat up in her seat and raised her right index finger, punctuating the important words for emphasis. “Your teacher, Ms. Jackson, called me this afternoon-ya.”

Kollie felt his arm stiffen. The dishwashing soap he was squirting onto the scrubber landed on the side of the sink, instead. “She . . .” He swallowed. “She called you?”

“Yes,” she said brightly. “The two of us had a nice, long conversation, all about you-oh.”

He tapped his toe on the tiles. This was not going the way that most talks about school did—she seemed genuinely excited about something. “Really?” he asked cautiously.

“Yes, really,” she said, laughing. “Don’t look so surprised, Kollie. I always knew you were capable of reaching your dreams. All you need is correct instruction and correct environment.”

Dreams? Now he was absolutely perplexed.

She stood up, pushed in her chair, and brought her plate to him. “She said she wanted to tell me herself about a beautiful essay you wrote about Bigazi, and the people who lived there before and during the wars. She said it was one of the best in the class, and that she is going to ask you to read it at the academic excellence assembly at the end of the month. She said that when you described the children in church, planting and harvesting groundnuts and cassava leaves, the beauty of the rivers, the quiet at dusk, and the aimless bullets that tore through compounds in the dead of night, it almost brought her to tears-oh.” She was standing close to him now, but her eyes had a faraway look to them. She took his hand. “I know I don’t know how hard it has really been for you here, to adjust to the new culture. They say that America is the Land of Opportunity, and I suppose that it is. If you want to better yourself, they will give you the opportunity to do so. But if you want to destroy yourself, they will give you that opportunity too.”

The energy coming from her eyes was too strong for him. He looked at the floor.

“And I know for black boys, they will convince you that it’s in your best interest to destroy yourself.” She sighed. “I don’t know why the whole world over, the worst thing to be is a black, but that is how it is. Especially in this country.”

He wanted to leave so badly then. That feeling he had had all week, of a scream eating his gut inside out, was bubbling in his belly again, and he didn’t know how much longer he could control it.

She grabbed his other arm, more forcefully than before. Then she brought his chin up, so he had no choice but to meet her eyes. “I am just so glad you are now making the choice to better yourself,” she said quietly. “Your father and I, the whole family, really, we have always had such high hopes for you. Angel is smart, and she works so hard . . . but she doesn’t feel like you do.” She placed a hand on his chest, and his heart pounded even faster. “You feel everything, which is why it is so hard for you, I know. But it is also why you are meant for great things. And it makes me so happy that you have not forgotten home. You are our black diamond, Kollie. And you are just beginning to shine.”

She was crying now. He swallowed the lump in his throat and wrapped his arms around his mother. He wanted so badly to tell her about everything, but he wanted her to be proud of him more. Let her have one thing in her life, for a moment at least, that made her happy.

“I love you, Ma,” he said as he rubbed her back.

CHAPTER EIGHT

KOLLIE THREW THE FIRST PUNCH.

Midway through the academic excellence assembly, while Kollie was seated on the stage waiting his turn at the mic to read the essay Ms. Jackson loved so much, he saw Clark push Sonja off the fourth row of the bleachers. She landed with an unceremonious thud and screamed, interrupting the principal’s long monotone speech on the importance of focus and integrity in classwork.

“What the hell is wrong with you niggas?” Aisha yelled, leaping down two aisles of the bleachers to help her friend.

“You stupid jungle bitch,” Henry snapped back.

Sonja was moaning on the gym floor, holding her right thigh in pain. Several teachers were looking on in confusion, barely masking their fear.

Before he could think about it, Kollie was off the stage, on the ground, and running toward Sonja. When he got to her, he saw that her face was stained with tears, and that her left shoe had fallen off.

“I’m okay,” she said to him as he leaned into her. “I’m okay.” She was wearing a spotless white cropped shirt and tight blue jeans, and she smelled of flowers.

“Hey, ma. Are you sure?” he asked.

“Yes.” She nodded. “I just . . . need some help getting up, that’s all.”

It was the longest private exchange they had ever had.

He nodded and held out his hand. She smiled at him and was moving her hand to meet his when Clark shouted, “Keep your hands off her, you sick monkey nigger.”

Kollie flinched and then grasped Sonja’s hand.

“I said hands off! Or I will beat you and your tiny black dick all the way back to—”

Kollie dropped Sonja’s hand, stood up, and lunged at Clark with all his might. He found that his fist was endowed with a kind of terrible force that stunned everyone around him. In his mind, he saw white hands pummeling Clark in the stomach, heard him wheezing in pain, then crumpling down the locker room wall, defeated. His ears rang with the bitter twang of Eddie’s voice: I’m the one in charge here, the one who you can either talk to respectfully or beg for your goddamn life. He shook his head, to shoo it away. Who’s the fucking pussy now, you little nigger? the voice said louder. It was Eddie’s voice. It was his voice.

* * *

—

Kollie sat alone in the living room later that night, the glare of the television his only companion in the house. His parents were both working, and Angel was at a friend’s place, working on some project.

“Yes, Bill, we’re reporting live here from Brooklyn Center High School tonight, from the scene of a brutal fight that broke out between students at an all-school assembly this afternoon,” said a young white woman dressed in a button-up white dress shirt and gray blazer. She was standing in front of the main doors to the school, which you could barely see, it was so dark now.

Kollie leaned over and turned up the volume.

The newscast cut back to the middle-aged white anchor in the studio, speaking to the television monitor behind him.

“Liz, I understand that the school’s director of security was wounded in the altercation, as well, is that right?”

The young woman pressed the hearing device in her right ear and scrunched her face, ostensibly listening to the anchor’s question as it traveled through the digital ether. “Yes, that’s right, Bill,” she said after a moment. “He was trying to break things up and restore the assembly to some kind of normalcy, when he got caught up in the fight. I’m actually standing right here with him now, as he has agreed to tell us a little bit about what happened.”

Kollie gripped his right hand with his left as the camera panned to the woman’s right to bring the image of Eddie into focus. That motherfucker found a way to weasel himself into everything.

Eddie leaned into the microphone. A blue bar on the screen read, EDWARD VAZER, DIRECTOR OF SECURITY, BROOKLYN CENTER HIGH, below him. “Yeah, well, the disruption started out as one between two students, but unfortunately evolved into a melee with more than ten. We had to take one student away on a stretcher, and three more were hospitalized. The student who started the incident has been suspended—”

Kollie sucked his teeth. He didn’t know that Eddie was even capable of using words like melee and disruption. Maybe someone had coached him before his big on-screen debut. He laughed at the thought, despite himself. These white people were crazy; he wouldn’t put it past them.

“And you were injured as well, is that right?” the reporter was asking him.

The camera pulled back to show Eddie’s right arm in a sling.

“Yeah, I’m all right,” he said, bravado rolling off him. “I had a few injuries that needed tending to at the hospital, nothing serious. I should be all healed up in a few days. The main thing is that we effectively stopped the fight and prevented further injury to students—most of whom were simply gathered for a regular assembly at the school and had no interest in participating in or witnessing violence.” Eddie looked directly at the camera then, carefully enunciating each word. “We take student safety very seriously here at Brooklyn Center High School. In fact, it is our top—”

Kollie leapt up off the chair and screamed at the screen, “Bullshit!” He brought his face so close to Eddie’s, spit was flying on the image of the other man’s face. “You lying piece of dog shit! Don’t give a fuck about me, Clark, or nobody in that fucking school!” He could still feel Eddie’s hands on him, strong-arming him to the ground away from Clark, twisting his arm so hard he feared it would break. And then finally, when things had calmed, being handcuffed, and dragged up again to standing, whipped around to see Eddie’s self-satisfied face staring into his, saying, “That’s enough, now, son.” I’m not your goddamn son! his brain had screamed, but his mouth and body were too wracked with pain and exhaustion to say it.

Bill the anchorman was now talking to Eddie. “We talked to some students there tonight who preferred to remain anonymous and did not want to appear on camera, who said that the atmosphere at the school has been very tense there for some time now—especially between the African American and African immigrant students.”

Eddie’s mouth pinched into a thin line, which caused Kollie to snort. “Oh, you don’t like that, do you, you little pussy? Somebody talking truth on your employer, shitting on your paycheck-oh?” He took a step back from the TV and crossed his arms.

“No, I wouldn’t characterize it that way at all,” he said quietly.

“Eh-menh!” Kollie exclaimed.

“There have been some tensions at the school, certainly, but I would say no more than what you might find at any other, normal school.”

“Bullshit,” Kollie said again.

“Okay,” said Bill back in the studio. “Okay.”

“Look, we’ve got kids with all kinds of issues, with difficult family lives, poverty and violence, and they don’t know the best way to deal with their problems. Which is why a limited few resort to violence, and have ruined it for everyone, on this occasion. But the principal is working hard on her new zero-tolerance-of-violence platform, and these disruptive elements will be dealt with, are being dealt with.” Eddie focused his needlelike green eyes outward, and Kollie swore he could feel them pressing on him, pushing on his skin for blood. “They have been removed, so that they can no longer endanger innocent bystanders, who are here to learn and positively contribute to our community.”

Kollie shivered involuntarily. His parents had not heard yet about the suspension, or his phone would already be blowing up with more than texts from Lovie and Tetee. From Angel, who was hiding out at a friend’s house. The school had surely left messages for his parents, but they could only check their phones on the rare breaks at work. There would be hell to pay when they did, however. Especially since he had sent Clark to the hospital.

“And I want all your viewers to hear me clearly when I say this, Bill: Brooklyn Center High is a safe pl

ace for all. This was an isolated incident, which we have now contained. We never have and never will condone violence here. Our number one concern is creating a safe, welcoming, and engaging learning environment for our students,” said Eddie.

Kollie couldn’t listen anymore. He leaned over and turned off the television. Then he massaged his right knuckles, which he had bruised from punching Clark so hard and so many times, and closed his eyes.

CHAPTER NINE

THE AIR WAS FRIGID, hefty with the coming frost. It was a little after five in the afternoon, and the daylight would not last much longer.

Kollie walked steadily westward, the thought of his destination moving his feet forward. The team would be preparing for the state tournament they had recently qualified for—the first time in more than twelve years. Coach and X (mostly X) would be running them hard, he knew, with speed and endurance drills, zone simulations, passing and defense moves. They would all be tired, but exhilarated about the prospect of winning against some of the best teams in the state. Of being better than they, or anyone else, ever thought they could be. A team of black boys who no one thought would really amount to much. And now look at us! Kollie thought proudly. Then he frowned, spit on the ground, and revised the sentence. And now look at them.

As the hard November earth crunched under the weight of his Timberlands, he saw Brooklyn Center High School looming to his right. He grimaced before he could think about it. He was coming through the back way, appraising the school from behind. Its windows looked on at him dimly, holding little light. The gray walls seemed taller, more imposing than he remembered. A cold gust of wind kicked up and blew in his eyes; he shielded his face with his hand and pushed on.

See No Color

See No Color Dream Country

Dream Country