- Home

- Shannon Gibney

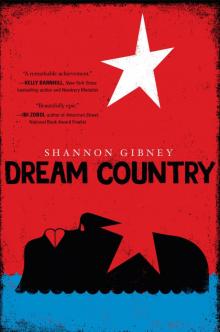

Dream Country Page 8

Dream Country Read online

Page 8

“Lies!” Fortee shouted. Then she took another few steps toward him and spit at the man’s feet. “You are ruining all of us up and down the St. John with your wicked, wicked taxes! They too much-oh.”

Togar turned away from the scene, fully hidden again by the tree. His sister had gone too far this time. And Gardiah would not be able to save her.

Togar heard the unmistakable sound of a slap. It echoed across the wide expanse of the village center, silencing even the hornbills whining in the forest. Togar forced himself to look from behind the tree again.

“Heathen bitch!” another soldier shouted down at Fortee, who was now cowering at their feet. “Forget your place again, and we’ll take you with the men. After we have our fun with you.”

Togar pressed his eyelids together and felt a tear squeeze out the side of his eye. Inside his chest, his heart thumped like the loudest drum on the longest night of the harvest celebration. Find the strength. She is your sister.

From his place in the line of men, Gardiah fell forward on his knees, brought his hands together in prayer, and appealed to the soldiers in a voice that made Togar’s skin prickle. “Please,” he said, “I beg. She is my wife.”

The soldier who had called her a “heathen bitch” smiled ruefully and approached Gardiah. “You have the misfortune of wedding this beast?” He leaned forward and cupped Gardiah’s chin, then gestured back to Fortee. “How can you get any joy from plunging your feeble little cock into her foul hole every night?”

Fortee appeared to have finally come to her senses and crawled back from the soldier who had slapped her. Togar saw the fear in her eyes, and for once he was grateful for it. It might save her life and preserve her womanhood.

But the soldier was not going to let her go that easily. He took a long step toward her, grabbed her by the hair, and whispered something only she could hear into her ear. Togar could imagine well enough what it was. Fortee writhed under his grip and shook her head.

As Gardiah looked on in horror, the other soldiers began to laugh.

There had been many times that Togar had imagined a moment like this, had fantasized about, really: The accomplished and arrogant Gardiah, finally taken down a notch, forced to face his own impotence. Growing up under Gardiah’s shadow, it had been hard for most boys in the village not to feel resentful. But now that the moment was here, Togar was both ashamed and irate. These pekins were nothing but a bunch of thugs from the lowliest of the Congo people, puffed up by the little power granted to them by their superiors. Togar tightened his right fist, wanting more than anything to pummel each of them to a bloody pulp.

Another soldier walked to Fortee, stuck his face in hers. “A woman like this could never obey her husband,” he said. “It must be like a piece of bush meat you can never really chew. But still, you keep on chomping and chomping, hoping your belly will fill somehow.” The man, who was stumpy and even a bit fat, looked around at his companions for their agreement. The bastards let their laughter ring out across the savannah.

The fat soldier walked back to Gardiah. “I feel sorry for you, my friend. So sorry that someone has apparently sold you a false bill of goods. You thought you were getting a nice, fat, juicy swine, but instead you got the sickly grasshopper.” He made an exaggerated sad face. “This world is so unfair, isn’t it?”

Gardiah met the soldier’s eyes, but Togar could see that he didn’t know what to do.

“Isn’t it?” the bastard demanded again, sneering at Gardiah.

This might have been the first time in his life when Gardiah felt completely powerless over someone else. Everyone knew he had a soft spot in his heart for his fiery, ever-loyal third wife. And then there was also the matter of Fortee’s new pregnancy. Gardiah and Fortee had only told Togar and their parents of it—until the baby grew, they said, and they knew it was really coming. Fortee had already lost two babies, one a miscarriage and the other in childbirth, so caution was called for. And if these men did what they threatened, it could not only harm Fortee, but the life taking root inside her, as well. Gardiah hadn’t said so, of course, but Togar knew him well enough to know that such a thing would kill him if it came to pass—to know that his baby had been wiped out by some idiot Congo men, that they had violated his wife’s womanhood, and that he had not been able to do anything to stop it.

Gardiah hung his head. “Ye-yes,” he said.

“Yes, what?” the soldier demanded, prodding Gardiah with his rifle.

“Yes—” Gardiah stammered.

“And you will look at me when I am addressing you, boy!”

Gardiah’s face flashed with anger and then, just as quickly, fell back to its docile state.

This is what the demons teach us to survive: to become two people at once. To hide ourselves in plain sight. What kind of sick learning is this? If Togar had had a gun in that moment, he would have shot the bastards dead—all of them, without remorse. A bullet in each of their foul heads. For making them learn the terrible necessity of two faces. Right between each of their eyes as they begged—

“Yes,” Gardiah said, looking the evil man in the eyes.

“Yes, what?”

There was a long moment, as Gardiah discerned what the man was truly asking of him. “Yes, sir,” he said slowly. “I get no joy from plunging my cock—”

“Your what?”

“My feeble little cock into her.”

The bastard looked surprised then, that he actually had the power to persuade a man to publicly destroy his wife and himself this way. He pointed to Gardiah, looked at his friends, and began to laugh.

“I knew it!” he exclaimed, jumping up and down in a kind of happy dance. “I knew he believed deep down that his wife was a beast! It’s as the commissioner always says: The country people only need some encouragement toward the correct path.” He patted Gardiah on the back, while his friends laughed along with him.

Gardiah hung his head farther.

Togar felt like he would vomit.

All the fire had gone out of Fortee, and she sagged under the soldier’s grip.

“Stand up!” the soldier yelled.

And then she started crying.

“Stop it! You will stop this embarrassment now, you monkey bitch!” The soldier grabbed her and dragged her across the earth to Gardiah. “You brought this embarrassment upon yourself, upon your husband, did you not?”

Fortee shook her head, weeping louder, almost uncontrollably now.

“Yes, you did! You did! Because you are not a good monkey bitch. You are not a good wife. You do not listen to your husband. And besides that, your hole is dirtier than a latrine pit. Which is why this man wants to vomit each time he enters you. What kind of life is that for a man to lead? What kind of happiness can you provide him, besides the stirring of piss and shit in what should be his home?” The bastard shook Fortee with each vile word, and she seemed to disintegrate more, her wails became more urgent and higher-pitched by the minute. Togar had never seen her this way, so clearly undone, and it scared him.

Gardiah delicately moved to take her hand. His head was still down, staring at the ground and his fingers grasped, slowly, precariously, her own.

“What? What are you—” the soldier began, and then didn’t bother to finish his sentence. He noticed Gardiah’s quiet attempt to connect with his wife, and it spread rage across his pinched, doglike face. With a roar, he batted Gardiah’s hand away with his rifle butt and kicked dirt in his eyes.

Gardiah howled and dropped to the ground in pain.

Togar yelled before he could stop himself, and a few of the soldiers and some of the villagers turned toward the sound. He yanked the upper half of his body back around the tree, cursing in his mind. He was no help to anyone if he got caught. In fact, his parents’ pressure might go off if that came to pass. Both their children and son-in-law abused in one day would be far too much for their elderly

bodies to bear.

“Enough of this!” a soldier yelled. “We don’t have the time.”

The man sounded forceful, like he was a commanding officer, perhaps. If such beasts could even be commanded.

Fortee’s cries still punctuated the dry air. And now, they were accompanied by Gardiah’s sad moaning.

“Oh, calm down, Ross!” said another one. “The commissioner doesn’t pay us enough to forgo our amusements.” He laughed, and a bunch of soldiers roared in agreement.

“He hardly pays us at all. We need our refreshment to keep us going,” another soldier said, and Togar could hear the lascivious undertones of every word. If there was anything on this earth that disgusted him more than they did, he didn’t know what it was.

The soldiers made lewd sounds, and Togar could imagine far too well how they were approaching Fortee. If I were a true brother, I would stop them. If I had the strength of my father, my grandfather, all my ancestors, I would kill them now, without remorse or hesitation. Togar could feel his breath thinning, and he looked down at the cutlass he had carried all the way from the farm. Gut them each like pigs. If I die fighting, at least it will be an honorable death. My son and the child that grows in Fortee’s belly will sing songs of my bravery. As will the griots. He moved the cutlass stealthily from left hand to right and crouched. He would slit the throat of whichever one came nearer, and he would enjoy doing it. His family would be avenged, and the Frontier Force would think twice about bringing their foul, polluted stench into their village again.

“We make for Edina at half past the hour,” the apparent commander said again. “I don’t care what you do before then or how you enjoy yourselves. Just be ready to go and free of complaints.”

A soldier laughed. “More than enough time to partake in this backward hellhole’s most potent natural resources.”

Another roar erupted from the soldiers.

Togar could hear one of them not more than ten feet away, and drifting nearer by the minute. A drop of sweat fell into his eye and burned. He gripped the cutlass tighter.

“No!” Fortee screamed. “You cannot do this! You cannot!”

The sound of another slap. Then Fortee’s whimpering.

“We’re doing you a favor. We’re going to make you clean again. We’re going to wipe out the jungle fungus and malaria your monkey man here has been shoving up your hole all this time and give you the gift of Christian cock,” a soldier said. “The light of civilization will enter you, and you will be redeemed by the Light and the Word. You will be saved by the coming of Jesus Christ our Lord, Amen.”

The sound of the bastards’ raucous laughter screamed through the lonely village, mixing with Fortee’s hysterical cries and the sound of her kicking feet being dragged along the ground. She wouldn’t go easily, that much was clear. He hoped she somehow managed to claw out one or two of their eyes before they were through with her.

“I was last at Gede Pa,” one of them said. “Let me be first now!” Then the sound of a belt unbuckling.

Togar shuddered. How many Bassa women had they ruined like this? How many men had they pushed to madness?

More laughter.

Out of the corner of his eye he saw two of the soldiers pull Fortee roughly into the bush. Abandoning his former plan, Togar thought now that he would charge them and slice them open as they prepared to take her womanhood. The element of surprise would be in his favor, and he was sure he could take down at least one of them. Though he may be killed by the others, it would be worth it to know the bastards would think twice about attacking other villages. And his family, his ancestors, would sing songs of him. He readied his heart, calmed his mind. It is almost the moment—

“I will give you everything!”

The sound of Gardiah’s voice, strong but trembling, interrupted the rustling of the grasses.

“What now?” A bastard’s voice again.

Togar peeked around the tree and saw his brother-in-law standing and addressing the men holding Fortee, his face and eyes covered in dirt.

“Let her go, and I will give you all of my rice and cassava crop as well as my fowls and goats. I have one hundred dollars in taxes for you too.” Gardiah’s voice broke. “And I will go with you and work your rice plantation all year. I will make sure it makes the highest yields of anyone in Bassa—maybe even the country. I am well-known in these parts for my abilities with crops.”

Fortee shook her head, obviously taking in the full meaning of his words.

“No,” said the soldier who had insisted on being first with Fortee. “That is still not enough.”

But the other soldiers had stopped to consider Gardiah’s offer.

The man who seemed to be commander—the one they had called “Ross”—stepped toward Gardiah. “Now, that,” he said, “is the most reasonable thing I’ve heard any of you apes say all day.” He pressed a long, thin finger into Gardiah’s chest. Oh, how Togar wished he were close enough to chop off the sad, strident digit!

Ross turned around toward the rest of his men. “Sadly, my distinguished Unit Five, I think we must take this extraordinary boy up on his offer and enjoy the fruits of conquest another time.”

The men protested, but it didn’t seem to affect their commander. He simply held up a hand to them and turned back to Gardiah. “Yes,” he said. “I have been hearing about such a one as you described in these parts. Someone who has a magic touch with the crops and can make them grow like bush weeds.” He walked around Gardiah slowly, eyeing him up and down as you would a woman. It made Togar want to kill him all over again. “Yes, you’ll do fine, I think.” He cupped Gardiah’s chin like he was a child. “And who knows? We may even be able to return you to your insolent wife here for a few months out of every year.” Then he laughed. “Go collect the beasts and all the rice and cassava you can carry,” he told the village men, who had been standing in line all this time. They looked at the commander in confusion.

“Am I speaking Greek? Do you not even understand English now, you backward country people? Go now!” Ross yelled, his face reddening with anger. The men scattered and headed to Gardiah’s compound and the granary.

Once they were gone, Ross turned back to his men. “And you, go help them.”

The men stared back at him, not comprehending.

“Now!” the commander screamed. If it was possible, his face reddened even more.

The soldiers finally complied and shuffled after the villagers dejectedly, all the while muttering under their breath.

“Ingrates!” the commander yelled at their backs, as they took the longest possible time to walk to the granary. Then he addressed Gardiah again: “I hope you know how much the nation needs a boy like you, with your talents. We appreciate your sacrifice for the greater good. From this day forward, you will be considered a true nationalist.”

Gardiah uttered a barely audible, “Thank you, sir.” Then he looked at his wife, who was still his wife now, not the violated shell his wife would have been had he not acted. Togar knew that, for Gardiah, it would all be worth it to avoid that catastrophe. And Togar would take care of Fortee and the baby like they were his own. They would be safe and well cared for.

“No,” Fortee cried as she fell to the ground. She reached her long, thin arms toward Gardiah in a pleading gesture, but he shook his head. “No,” she cried again, and buried her head in her arms. Soon, he would comfort her. She would see—

“You behind there! You can come out now!” Ross yelled in Togar’s direction.

Togar shivered. He saw the future he had created in his mind of he and Jorgbor and Sundaygar caring for Fortee and her baby rapidly disappearing.

“I say, you there!” the commander yelled again. “Make yourself known. I know you are there. I know you are strong, but not strong enough to evade me. We need you on Commissioner Franklin’s plantation, serving your country like the

rest of your brothers. You will not be harmed if you come out right now.”

The edge of the bush where the soldiers had dragged Fortee was maybe five strides away from him. If he could launch himself from behind the tree, he could make it there before the vile man could catch him, and from there the forest would conceal him. He knew every branch, every fern, every kind of beast for miles. These bastards knew none of it, and even worse—they hated it. But this was Togar’s home, and he loved it. The land in turn loved him back, and that could make all the difference between survival and death, freedom and capture.

Togar heard the man’s strides on the dirt, rapidly approaching. If the bastard had his gun drawn now, he was a dead man for running, but Togar was ready to take that chance. He thought of Sundaygar kicking him during his baby dreams the night before, when Jorgbor had taken him to her breast to suck. Of how the light from the almost full moon had streamed in from a small crack in the thatch roof, making a bright beam across their faces. They hadn’t seen him watching them, hadn’t had to account for the weight of his love from his eyes.

“Van-an se m bada hweh oh gbehn ke m bada de,” he said under his breath. A billy goat has beaten me, but its horns cannot beat me again. Then he pushed off the redwood trunk and pumped his arms and legs as fast as he could.

“Stop, I say!” he heard someone yell behind him, and then felt something small and fast whip by his shoulder. He dashed into the bush and didn’t stop running till nightfall.

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

THE SMALL FIRE MADE strange shadows in the dark forest around him. Its flames greedily devoured the small sticks and dry leaves he had been able to gather. He would have to put it out soon or risk sacrificing all the miles he had put between him and the soldiers; but Togar was willing to take that chance in order to warm up and eat. A small lizard he had caught cooked on the stick he held in the flames. It wasn’t much meat and it would be tough, but it would do. Togar knew well enough what would happen if he didn’t keep up his energy: The soldiers, who would be well fed, would catch up to him quickly. No, he needed to maintain his energy in order to keep a quick pace. He would eat and then rest his legs for a few hours before starting again.

See No Color

See No Color Dream Country

Dream Country